Reuters

As challenging and oversimplifying as it is to distill the complexity of science diplomacy, every year the Conference of Parties (COP) is dominated, from its beginning, by a prevailing theme which takes precedence during negotiations. In last year’s COP held in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, which was also dubbed the ‘African COP,’ climate finance took centre stage. Following years of disagreement, the coalition of countries from the global South secured a fund to address losses and damages caused predominantly by climate change attributed to industrialised nations.

The operational details of this fund are still to be discussed, and this will be a hot topic at COP28, which is already being termed as the ‘petrostate COP.’ Starting on November 30th, 2023, in Dubai, this conference will be chaired by Sultan Al Jaber, Minister of industry and advanced technology and special envoy for climate change of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and CEO of Adnoc, Abu Dhabi’s national oil corporation. Al Jaber is also the founder and president of Masdar, UAE’s Future Energy Company that invests in renewable energy.

When it comes to mitigation efforts, aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the president of the Conference embodies all the tensions within COP28, balancing interests to safeguard and commitments to fulfil.

Several observers believe that interests will by far prevail over commitments, and that the Arab COP will result in a global greenwashing operation amidst the approving applause of an assembly that will leave no room for dissent. "For over a decade, the UAE has targeted rights activists leading to the complete closure of civic space, severe restrictions on freedom of expression online and offline, and the criminalization of peaceful dissent,” Human Rights Watch states.

Sultan Al Jaber, Reuters

Whereas COP27 closed with a victory in terms of adaptation, with the establishment of the ‘Loss&Damage Fund,’ it also marked a complete failure on the mitigation front. In COP27 final document, fossil fuels are mentioned only once, referring solely to coal, and calling for a gradual reduction (phase down) rather than a complete abandonment (phase out). Thus, it would be somewhat unexpected, at least, for the demand to relinquish oil and gas to be stated for the first time during a COP by a host country whose economy entirely revolves on the extraction and sale of these resources.

According to the UNEP’s 2023 Production Gap Report, Adnoc plans to increase oil production from 4 to 5 million barrels per day by 2027, through a major 150 billion dollars investment. The company also aims to raise Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) production from the current 8,2 to 21,2 billion cubic metres by 2028. This will involve building a new infrastructure that will be able to transport 13,1 billion cubic metres annually to Asia and Europe.

The Italian energy company Eni, publicly financed, has recently struck a deal with Qatar, UAE’s neighbour, for LNG supplies until 2053, by which time climate neutrality should have been already achieved three years prior.

This contradiction represents the elephant in the room in negotiations. There are no alternative ways to escape the ecological trap that we have constructed around ourselves over the past two centuries. It is imperative that we cut the production and consumption of fossil fuels.

After the hottest September and October on record, with 2023 on track to become the hottest year in the history of human civilisation, November 17th, 2023 marked the first day when the Earth’s average temperature reached 2°C above the pre-industrial average. Although the year’s global average will remain below 1,5°C, this first breach is a forewarning of how temperatures are relentlessly rising, and the time window for reverting this trend is rapidly closing.

The emissions from the energy sector (almost 37 million tons of CO2 in 2022) account for three quarters of all emissions human societies release into the atmosphere each year (over 50 million tons of CO2eq).

Reports produced by the scientific community (IPCC, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) and international institutions (from UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme, to IEA, International Energy Agency) are numerous, consistently reminding us that climate change poses the most looming threat to civilisation humanity has ever faced. They emphasise that to counteract this threat, it is necessary to reduce greenhouse gas emissions rapidly and drastically.

As reported in a document by the UNFCCC (the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change), to stay below 2°C of global warming compared to the pre-industrial levels, anthropogenic emissions must drop by 27% by 2030. To remain below 1,5°C, emissions should be reduced by 43% by the end of this decade.

Another way of framing the issue is considering how much CO2 emissions we can still afford to release into the atmosphere before surpassing critical temperature thresholds. This concept is referred to as ‘carbon budget,’ and our current carbon budget is definitely narrow.

To have a 50% chance of staying below 1,5°C from 2020 to 2030, we should avoid emitting more than 500 gigatons (Gt) of CO2. This implies that if current emission levels are maintained, we will likely exceed the target of 1,5°C set by the Paris agreement by the end of this decade. To have a fifty-fifty chance of remaining below 2°C, the carbon budget for the decade would be around 1150 Gt of CO2. According to the IPCC, however, between 1850 and 2020 we emitted approximately 2.390 Gt di CO2, resulting in a warming of the planet by 1,1°C: nearly half a degree of increase for every 1000 Gt of CO2.

These data have been known for a while, yet they are not making an impact on decision-making processes of businesses and governments. The UNEP Emissions Gap Report, published every year just before the Climate COP, assesses the commitments and climate goals contained in Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Individual countries must periodically update these documents, in line with the Paris Agreement. Altogether, plans and declarations, despite significant differences among countries, points towards a global temperature rise between 2,5 and 2,9°C.

Even in the most optimistic scenario of current climate plans, the likelihood of limiting warming to 1.5°C is only 14%.

— UN Climate Change (@UNFCCC) November 20, 2023

A new @UNEP report warns: Nations must urgently reduce emissions or we might face global warming of 2.5-2.9°C.

More: https://t.co/RInqRuCbzV#COP28 pic.twitter.com/2d6tKVk8mk

The UNFCCC document also reports that the current plans outlined in the NDCs would consume, by 2030, 87% of the carbon budget needed to stay below 1,5°C (leaving only 70 Gt of CO2 available to use after 2030), whereas depleting 38% of the budget associated with a 2°C scenario. By 2030, emissions would only drop by 2% compared to current levels, remaining around 50 Gt per year.

It is evident that the window for taking action, both in terms of time and opportunity, is rapidly closing. It is equally evident that fossil energy we consume needs to be replaced by low-emission energy sources. During last week’s meeting in San Francisco between Joe Biden and Xi Jinping, the leaders revealed that United States and China, the two most emitting countries in the world, will cooperate on climate issues and commit to tripling their renewable energy capacity by 2030, primarily through increased installation of photovoltaic and wind energy.

A few weeks earlier, IEA’s Net Zero Roadmap had pointed towards the same objective. Both IRENA (the International Renewable Energy Agency, headquartered in Abu Dhabi) and COP28 Presidency have now aligned with this goal, and the latter has placed it at the beginning of a letter sent to the convening parties.

According to a report by Ember, the sum of individual nations’ plans is already compatible with the doubling of renewable energy capacity by 2030, increasing from approximately 3.400 GW to 7.300 GW. However, in some countries, notably China, these goals will be achieved ahead of schedule. Thus, with additional effort, reaching 11000 GW by tripling renewable energy capacity is a feasible target with decisive national policies, the Ember think tank states.

NEW | Government targets already align with a doubling of global renewables capacity.

— Ember (@EmberClimate) November 21, 2023

But these targets do not account for the recent renewables boom.

A TRIPLING is within reach by maintaining the 17% growth rate achieved since 2016#3xRenewables #COP28https://t.co/kYN0h9BYUt pic.twitter.com/9NC1lv0SgU

An agreement on renewable energy is a realistic achievement that can be expected from COP28. However, it will not be useful if it merely serves as a façade masking inaction regarding the reduction of oil, gas and coal consumption and emission. Renewable energy must not accompany fossil fuels; it must replace them.

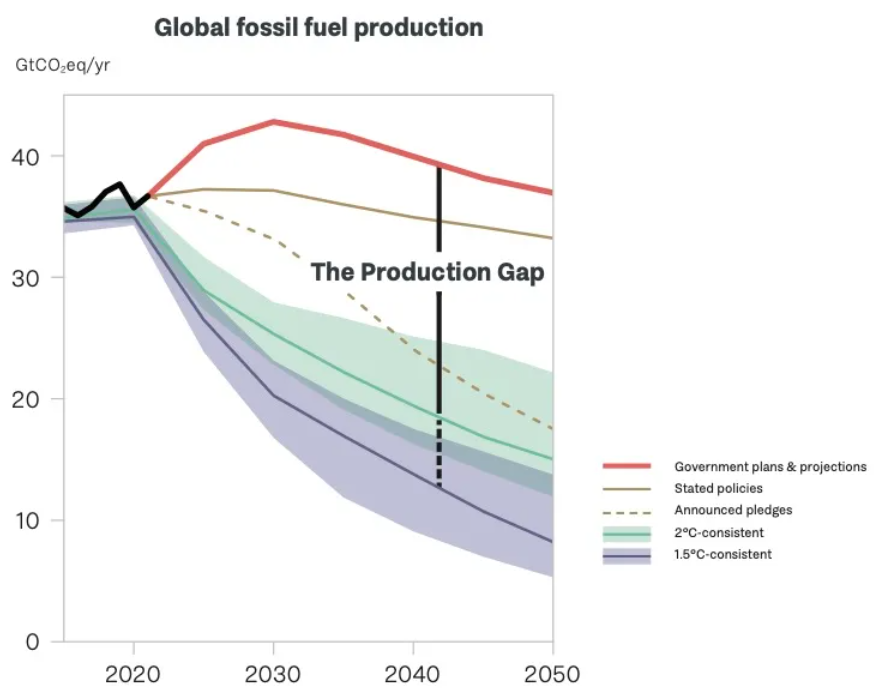

The Production Gap Report states that not only the UAE, but national governments’ plans in general are aiming for a global increase in the production of fossil fuels, which by 2030 would be double what is needed to keep emissions and temperature rise below critical thresholds, in line with the Paris Agreement.

Production Gap Report 2023, Unep

“Those who say that achieving climate goals is impossible are on the wrong side of history, I believe,” argued Fatih Birol, director of the IEA, in a recent interview. To paraphrase his words, even those who slow down the process of achieving those goals are on the wrong side of history. in a few weeks, we will understand where COP28 will stand.

This article was translated into English by Sofia Belardinelli. The original version of this article is available here.

ALSO READ: