We were nowhere near the finish line. Far from it. The fight against plastic pollution is still a long way from being won, on land, and especially in the seas. But some progress has been made over the years. Starting with the approval of specific standards at the European level and the launch of global initiatives to reduce the circulation of disposable plastics, to research and use more easily recyclable plastics, to clean the seas, rivers, and oceans. A series of initiatives, from local to global, are yielding concrete results, even if still far from having a real impact on the environment and our health. And that is because the plastic produced and released into the environment is indeed a lot.

Alongside the European Strategy for the reduction of plastics launched in January 2018 and the directive on the single-use plastics ban, a Plastic Tax was to be adopted in several countries, including Italy, and a series of other initiatives. There were laws against plastic bags and straws approved in California and New York State and similar provisions in hundreds of other American cities. There was a very tough law against the production and use of plastic bags passed in Kenya in 2017, and an equally tough one in Rwanda in 2018. As a matter of fact, Africa is the continent with the highest number of national anti-plastics regulations, with laws passed in 34 countries. There are initiatives in several Asian countries, from Vietnam to Malaysia, from China to Indonesia.

Many think tanks and cross-cutting projects have emerged, sometimes including large multinational companies, such as the Global Plastic Action Partnership created within the World Economic Forum. Furthermore, many information campaigns have been launched, such as the National Geographic Planet or plastic and the actions put forward by Greenpeace and other environmentalist organizations. Something was happening, albeit amid opposing forces, such as the lobbying activities by the plastic industry, on one side, and a plethora of actors and stakeholders on the other. Even these latter sometimes find themselves divided among those who support recycling and those who believe that real change can only come from banning plastic production and usage because recycling can only go to a point in solving the problem.

On the occasion of Earth Day, on the 22nd of April, the non-profit association The Story of Stuff Project, part of the global movement Beyond Plastic, released a documentary, The Story of Plastic, visible on various streaming platforms. The trailer, below, gives a very graphic idea of the problem.

During the Covid-19 emergency, the issue became even more complicated. To contain the contagion, we need to systematically use personal protective equipment, such as masks and gloves. But there is more: Plexiglass or other plastic screens are popping up in many public places to avoid contact. Plastic cutleries and cups have become the norm again in bars, cafeterias, and many take-away food stores so on and so forth. These are mostly objects made from mixed materials, hardly recyclable and thus destined to go and increase the already immense mountains of waste that needs to be handled. And at the same time, these objects are considered indispensable to allow people to go back to work safely, to get on public transport, go to the office, sit in the restaurant and enter the shops.

It is enough to read the indications prepared by INAIL, the Italian National Institute for Insurance against Occupational Accidents at Work, to understand that disposable plastics will remain present in our public life for quite some time. And this will have considerable environmental consequences, difficult to estimate but undoubtedly significant given the amount of material each of us will have to use and throw away every day. Furthermore, given the reduced oil price, industries do not even see any economic incentive in trying to use and produce less plastic. An additional motivation, for large corporations, to resist the transition to an increasingly plastic-free world.

How much plastic is produced these days

Every year the European Union produces over 60 million tons of plastic. The Plastic Facts 2019 report published by the Continental Manufacturers' Association shows that there was a slight decrease compared to the previous year (-2.6 million tonnes). However, it is still enough to cover 17% of global production.

Globally, 358 million tonnes of plastic were produced in 2018. China accounts for the most significant fraction, over 30%, equal to 107 million tonnes, a figure that is double than the European one. The authors of the report point out that China is the country that has shown the highest growth in this sector in recent years. This trend is in line with its overall economic and industrial growth that has led the Asian country to compete with the United States for the role of top world economic power. These numbers are particularly relevant: the USA and China not only compete for the overall economic leadership. In the world of plastics, they are the first to produce and consume plastics and produce plastic waste.

Looking at the data, it is essential to clarify what we are talking about. There are many types of plastic on the market, made through various industrial processes with very different final characteristics. The figures presented in the report and used to draw our charts include all types of plastics. There are PMMA, polymethylmethacrylate, a family of products that include plexiglass recently brought to notoriety for the (very implausible) idea of using it to keep distance on the beaches. Plexiglass is, in fact, coming back in cafes and restaurants to shield people and avoid them from getting too close at the bar or while sitting at tables. Then there is PET, or polyethylene terephthalate, used to make food containers such as bottles. There is also silicone, used both as an insulator in the construction industry and a key component of many diverse soft objects. And then there is polyurethane, used among other things as a component of some fabrics, such as alcantara. And many more.

Plastic waste

Except for Japan, the primary source of waste everywhere in the world is disposable plastic from packaging. The data comes from the analysis of Conversio Market and Strategy, a German consultancy company specialized in the plastics industry. Conversio's own analysts stress the difficulty of performing this type of analysis due to the different data collection methods, their limited reliability, and the diverse waste collection and disposal systems in operation in different countries. Nevertheless, even without taking them literally, the data provide a clear picture of the fact that it is precisely the poor quality single-use plastic, that ends up in the bin after a rather short life. That same plastic we use everyday to wrap up our food and other products we buy.

The ability to recycle, giving waste a new life, varies significantly from region to region, as the graph shows. In this case, too, we have to take the data cum grano salis since some of them can be of limited reliability, according to Conversio. To perform a real comparison, there should be monitoring systems in place for the entire plastics cycle, from production to final waste. However, there is a high degree of variation from country to country. Furthermore, these data depend highly on rules and regulations, that while being quite stringent in the case of the European Union, are not as defined in other areas of the world.

A very clear outcome of the analysis is that limitations imposed by law are the leading promoter of change, as the good results in terms of recycling in Europe clearly show. Ten out of 30 European countries (here including Switzerland and Turkey), in fact, managed to achieve 95% reuse of plastic - net merely recycling. The ten countries are Switzerland, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Sweden, Finland, Belgium, Denmark, and Norway. The same mechanism is also behind another critical result: overall, in Europe, 41% of plastic for packaging comes from recycling. According to Conversio, this is due to the responsibility policies imposed on companies, i.e., the set of economic incentives and penalties that fall within the so-called extended producer responsibility (EPR).

The USA vs. China

The first producers of plastics and plastic waste are the two world superpowers. Compared to the United States, China recycles four times as much plastic waste and sends only a third of it to landfill. But it also produces the highest amount of plastics that are not adequately handled, ending up in poorly managed landfills, where they cause environmental damage. Finally, China also burns four times the amount of plastics than the USA (energy recovery) using incineration processes capable of producing clean energy according to EU directives.

This comparison between the two world giants clearly shows in which areas both will need to improve to ensure a less plastic-polluted future. The Asian superpower will have to improve its ability to intercept all plastic waste, reducing the amount that is poorly managed or not accounted for (3.9 million tonnes per year). The American counterpart will definitely have to invest in the implementation of a policy of separate collection and recycling of waste, following the path that has been successfully led by European countries over the last two decades. Given the growth of the American population, this becomes a crucial issue for the coming years.

Bioplastics

Over the last seventy years, the amount of plastic produced worldwide has almost reached 8 billion tons, as shown by the graph developed by Our World in Data and based on data from a study published in 2017 in the scientific journal Science Advances.

As it is stressed by all European initiatives in this area, the primary objective must remain to reduce the amount of generated waste. Alongside the reduction, the increase in recycling and other techniques to better exploit waste, one solution that has become widespread in recent years is the replacement of plastic materials of fossil fuel origin with so-called bioplastics. However, we need to make a clear distinction since this term means two different things.

The first family of materials that usually comes to mind is those products that can be biodegraded once their life is over, such as bioplastic bags that can be disposed of with other organic materials. However, bioplastics also include products that come from biological materials and not from fossil fuels. For this reason, they are also called bio-based plastics. In this case, they are not necessarily biodegradable. They might be, but, as a matter of fact, biodegradable bio-basedplastics constitute only a minority of the galaxy of bioplastics currently produced. According to European Bioplastic, the continental association of bioplastics producers, such different materials open the opportunity to provide a bio alternative to any fossil-based plastics currently on the market.

According to the same organization, in 2019, the sector was worth less than 1% of the entire world's plastics production. However, pointing out the positive side as it is in their best interest, European Bioplastic sees a growing trend, and it plans to go from the current 2.1 million tonnes per year to around 2.5 million tonnes in 2024, an increase of almost 20% of the total production in just five years.

While the quantities still do not seem sufficient to meet increasing demand from high growth countries, it is interesting to note in which sector bioplastics are most widely used. The European Bioplastics report says that 46% of bio-based plastics are used as packaging (both rigid and flexible). A percentage that rises to 59% in the case of biodegradable plastics. In other words, so-called bioplastics are already widely used in one of the most problematic sectors, creating the majority of disposable waste. Particularly when the plastic packaging is for non-indispensable uses: take-away meals, single portions, vegetable bags, and so on. On this front, therefore, even if numbers are still small, bioplastics can contribute significantly to reduce the weight of plastic packaging on the environment, mainly when adequately supported by regulations (as those banning single-use plastic bags.

And now what?

As we were saying, in this period of response to the COVID-19 pandemic, plastics have returned to the center of public discussion because much personal protective equipment is made of plastic, often disposable. Starting with masks and gloves, which we must all wear, or visors such as those that protect hairdressers and all workers in personal service centers, from dentists to beauticians. Plastic taxes have been put on hold. And, in many cases, recyclable bags brought from home are banned because considered less safe. However, a study recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine indicates that the permanence of SARS-CoV2 virus on plastics is still quite long - up to 3 days - and it lasts more than on other surfaces. Media are also full of stories of companies that reconverted their production cycles to meed the surge of demand for protective devices. These companies are now finding plastics is a great option to cope with the economic crisis.

There is an apparent conflict between the drive to reduce the use of single-use plastic and the need to increase it during these months and perhaps for years to come to contain the spread of the virus.

The Open Enterprise Report produced at the end of April by the Italian Politecnico di Torino (PoliTO) offers an estimate of the number of masks needed by workers in our country's various production sectors. For the Piedmont region alone, during the reopening phase of all activities, the Report indicates that about 76 million surgical masks will be used each month and nearly 8 million of the common non-surgical ones. This figure derives from two piece of data: the estimate of the regional workforce and the fact that the mask should not be worn for more than 4 hours in a row. In addition to the masks, 38 million gloves, 175,000 thermometers, and 21,000 plastic hair caps for those with long hair should be added per month. PoliTO estimates are based on ISTAT data - the Italian National Institute of Statistics - relative to the number of workers per region: Piedmont has about 8% of the Italian workforce.

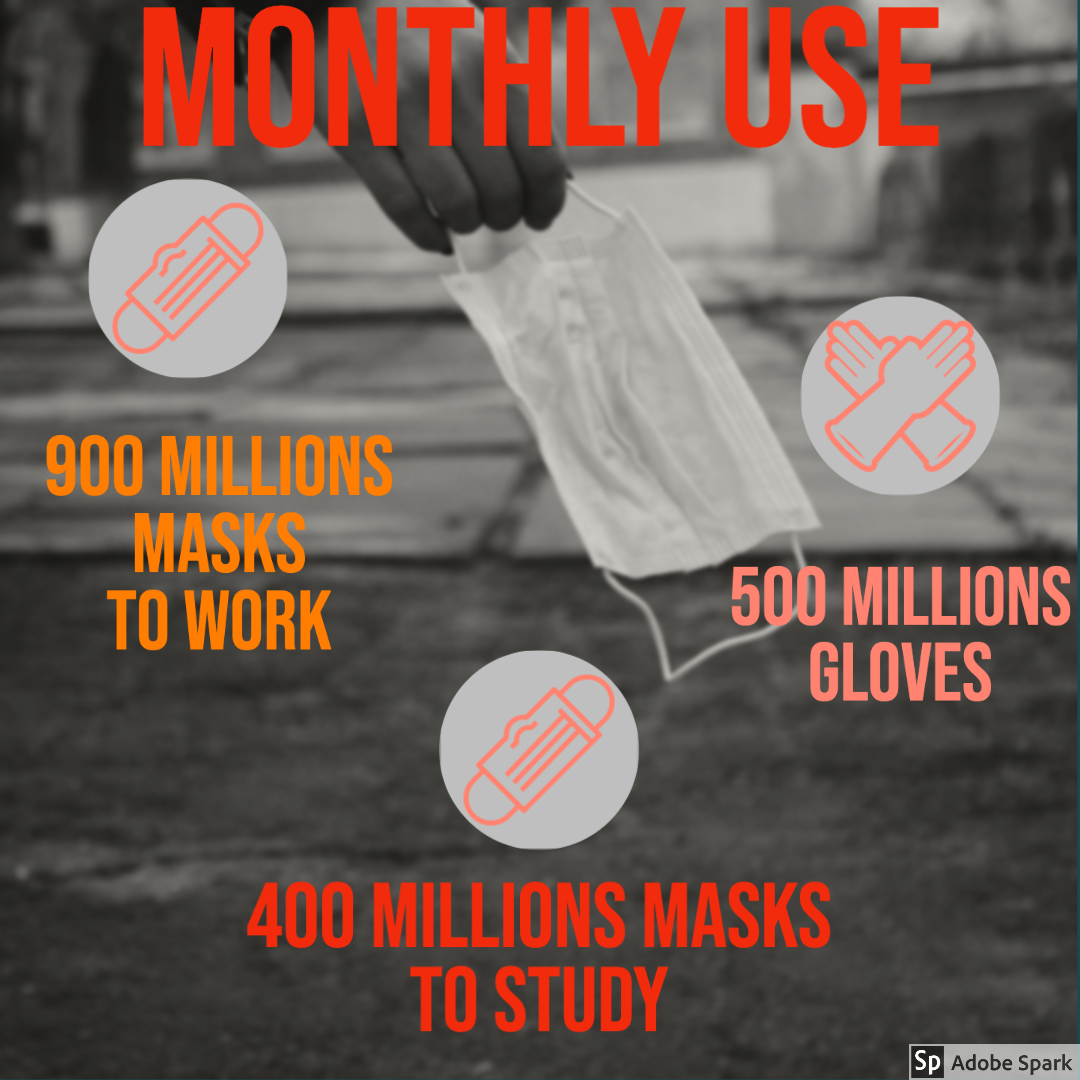

For this reason, PoliTo suggests that to be making an estimate on a national scale, we should multiply those figures by 12. We confirmed this calculation by using ISTAT data on the number of Italian workers (just over 25 million) and taking into account the smart working ones. Overall, we reach an approximate figure of over 900 million masks used every month in workplaces plus 100 million ones used by people in their daily activities. In addition to almost 500 million gloves. For Italy, only.

To these, we need to add the number of masks and other devices required to reopen the schools. The same Polytechnic of Turin (PoliTO) has published a Report with indications for the reopening of schools, where it is estimated that every student aged +6 years should wear 2-3 masks at school during one day. Considering the more than 8 million students who attend Italian schools every day, we can estimate well over 20 million masks used daily, for a total of 400 million per month. Not to mention the disposable lunch boxes with single-use plastic plates and cutlery instead of regular meals offered by school canteens.

Very substantial figures. Unfortunately, the only possible recommendation, at the moment, is the one coming from WWF and other environmental associations. On one hand, they are proposing alternative reusable devices, such as washable masks, at least for daily personal use outside the workplace. However, it is especially crucial to ensure that these plastic devices are discharged in the safest way to prevent them from being dispersed in the environment. Just considering the Italian situation, in fact, "If even just 1% of the masks were disposed of incorrectly and possibly dispersed in nature, this would result in as many as 10 million masks per month being dispersed in the environment," quotes the WWF in its statement. And it goes on concluding, "Considering that each mask weighs around 4 grams, this would result in the dispersal of more than 40 thousand kilograms of plastic in nature: a dangerous scenario that must be defused!”

An all-Italian think tank bringing together many companies and professional associations active in the circular economy, the Sustainable Development Foundation, has recently published the dossier Pandemia and some green challenges of our time. While not referring specifically to plastic waste, it draws attention to the fact that this period of contraction in consumption on the one hand and reduction of pollution on the other can also be a source of reflection, ideas, and reasoning. It can lead to a recovery in line with the philosophy and practices of the circular economy and not the linear economy, which necessarily involves intensive production and even large amounts of wasted resources.

A glimmer, a hint of hope, that goes along the same lines of thought of those highlighted continuously in the past weeks by a large part of the civil society committed to the environment. It goes with trying to prevent the pandemic from producing a huge step backward in environmental protection policies and practices. On the contrary, say many of these organizations, we now have an invaluable opportunity to rethink the fundamental structure of the current production system and development model.