“I don’t photograph war, I tell love": Giles Duley on storytelling, resilience, and the power of empathy.

Foto di Alessandra Lazzarotto - © Università di Padova

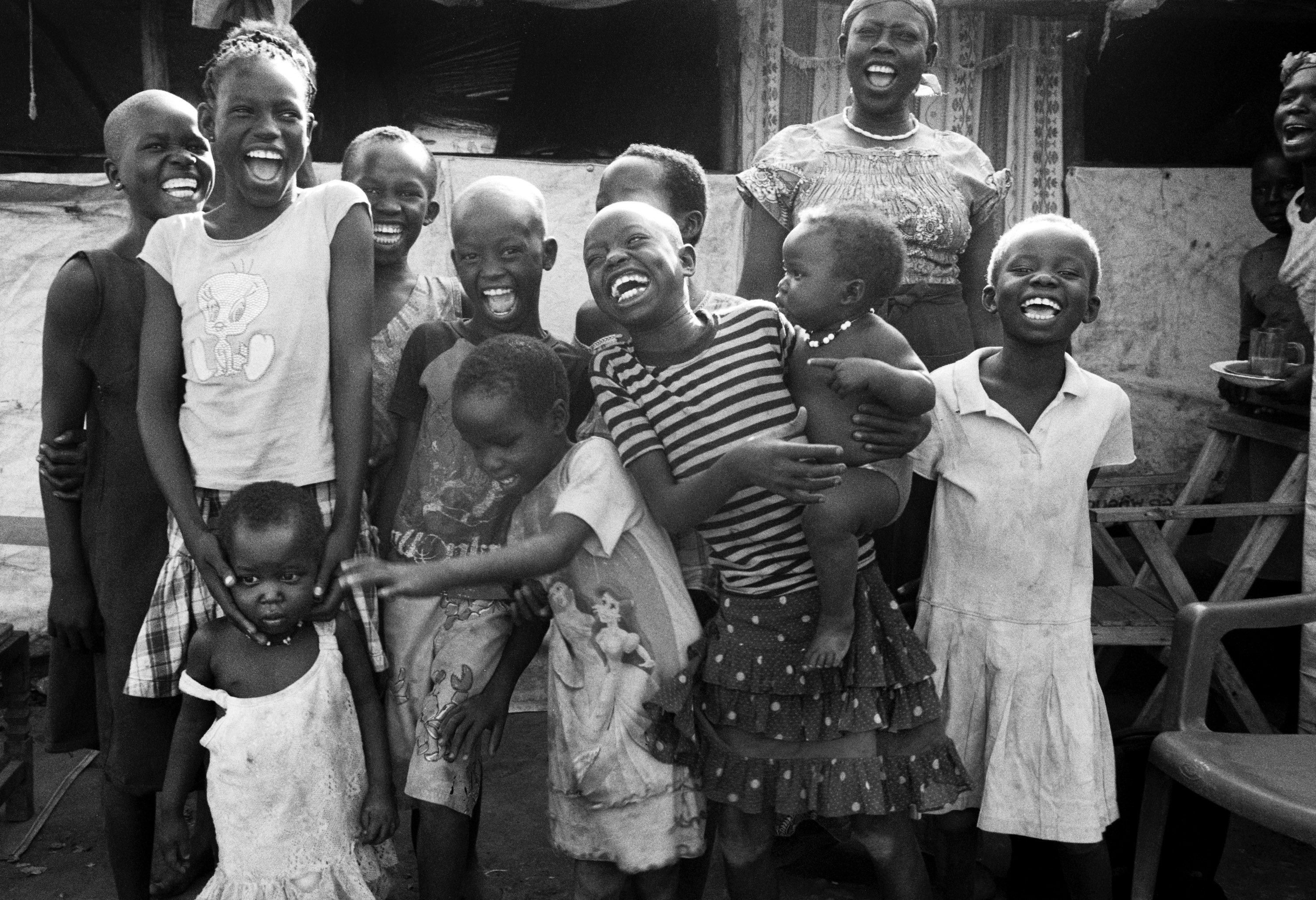

“People call me a war photographer, but if you look at my work, there is no war. What I photograph is love". Giles Duley doesn’t fit the stereotype of the hardened conflict photographer. Yes, he has worked in war zones for over two decades, where he has seen the consequences of famine, violence and torture. And yes, in 2011, he stepped on an explosive device in Afghanistan and lost both legs and an arm. But Duley, who visited Padua for a public talk, insists that neither war nor pain defines his work.

“What connects me with the people I photograph isn’t suffering: it’s resilience”, he explains. “Resilience is life’s gift when we go through difficult times”. For Duley, what matters is not the injury, but what follows: 46 days in intensive care, 37 operations, learning to walk again. “That was when I received the gift of resilience”, he says.

Duley doesn’t want to centre his narrative on himself. “I was injured doing a job I chose, but not everyone has a choice. Two months after my incident, a seven-year-old boy stepped on a landmine in Kandahar while walking to school, losing a leg and an arm. I remember crying as I took photographs of him, 18 months after my incident. These are the stories that really matter, and I don't want to put them in the shadows, talking too much about my own”.

Duley’s work goes beyond photography. He describes himself more as a storyteller – one who seeks intimacy and connection. “I want to feel that there was a real relationship between the photographer and the persons”, he says. “A good image must have a story. Not beauty, not clever lighting – just truth, narrative, empathy”. Recently, Duley found unexpected confirmation of his mission in an unlikely source. In an interview with Joe Rogan, Elon Musk said that empathy was the cause of the collapse of Western civilisation. To me, that was a rallying call. It meant that empathy – and by extension, stories – are still powerful. If that’s what people like Musk fear, then I must be doing something right”.

His storytelling method is rooted in human connection. “I always eat with people before I photograph them. We cook together, share meals, build trust. That way, they are no longer ‘subjects’ – they become friends”. Duley often returns to the same places over the years, documenting with patience and respect the evolution of the lives of the people he has portrayed. “The story doesn’t end when we leave. For them, it continues. Sometimes, the story is that nothing has changed”.

Asked whether he believes the world is becoming more violent, Duley pauses. “What’s changed is visibility. When I was a child, we watched the news once a day: now, we see suffering 24/7 on social media. That’s good – it means awareness – but it also overwhelms people. And when people are overwhelmed, they don’t act”. Overwhelm, he warns, is not neutral: it’s political. “Steve Bannon called it ‘flooding the zone’: creating so much chaos that people shut down. That’s why I think the best thing is to focus on what you can control each day”.

Even after years of work, Duley knows that change is a slow process. He explains his philosophy through what he calls his ‘burning house theory’: “If you’re walking down a street and see someone screaming from a burning window, most people will try to help. They won’t ask if that person is white or black, Christian or Muslim, refugee or citizen. They'll act. That's what we need to remember".

This is the reason why Duley believes that art, exhibitions, and storytelling – even when they don’t move crowds – can still matter. “I wish I could stop all the wars with a photograph, but I know that won’t happen. What I believe is that maybe my work will not change the world, but it might reach the one person who can.”

Even in a broken world, Giles Duley insists on believing in people. “We are living through a difficult time, but I still believe in humanity”. And amid all the darkness he has witnessed, what Duley chooses to see and document is not despair, but care. “In a refugee camp or a war zone, I find love. A grandmother brushing her granddaughter’s hair. A mother feeding her baby, a father doing homework on the floor with his kids. That's what my work is about: Humanity at its best”.

This article was originally written in English, as the interview was conducted in that language. Since Il Bo Live does not have native English speakers on staff, we edited the text with the support of an AI-based language tool.

Questo articolo è stato scritto originariamente in inglese, poiché l’intervista è stata condotta in quella lingua. Poiché nella redazione de Il Bo Live non ci sono madrelingua, abbiamo rivisto il testo con il supporto di uno strumento linguistico AI.