SCIENZA E RICERCA

Italy was at the centre of a metal diffusion network during the Copper Age

Between the 4th and 3rd millennium BC, known as the Copper Age, Italy was at a crossroads with its complex network of diffusion and exchange of this metal that had developed earlier than thought. Finding published in the scientific journal Plos One from studies conducted by Andrea Dolfini of the University of Newcastle, as well as Gilberto Artioli and Ivana Angelini of the University of Padua.

New research conducted in the past decade has shown that the extraction of cupriferous minerals and the processing of copper in prehistoric Italy began earlier and with more complex technologies than previously believed. But too few details are known about the routes of diffusion and the methods of exchange of this metal south of the Alps. This is why the scientist from Padua are working to better understand the extent of copper imports and trade in Neolithic Italy.

To reconstruct the exchange routes and copper processing sites, as well as the timing, the team examined 20 copper objects that include axes, halberds, and daggers found in central Italy. "We have recovered and analysed finding that had already been dated according to the context and type and which are now preserved in various museums in central Italy, such as Florence, Arezzo, Siena, and Grosseto" explains Gilberto Artioli, from the University's Geosciences Department, in the Il Bo Live article. “The dating of such finding is something quite complex as the metals cannot be dated directly. Therefore we have a chronological indication from archaeological studies, which conducted chemical and isotopic analyses of lead traced from within the origin of the metal", continues Artioli.

If we are talking about copper, what does lead have to do this? “All copper findings contain some traces of lead impurities. The relationship between the concentration of lead 204 and its radiogenic isotopes (206, 207 and 208) can be used to obtain information on the origin of copper itself. The ratios vary within different fields depending on their age and, in practice, they become a blueprint of different Italian and European deposits. Once the isotopic ratios of lead have been measured, all we need to do is to compare them against a database as complete as possible from the mines, to understand where that particular copper has come from. ”

By comparing the archaeological data and the isotopic signatures of copper objects within the mining areas as well as the distribution of the archaeological sites, it has become possible to trace the routes of prehistoric copper in Italy.

"The first systematic application of the findings examined from the analysis of the lead isotopes revealed that central Italy was an important metallurgy developed long before the Etruscan-Roman era. Copper was mined and worked as early as the second half of the 4th millennium BC, mostly in Tuscany. We had already suspected this when we examined the axe of the Iceman, known also as the Similaun Man, or "better known as Ötzi, a man who had died around 3200-3300 BC. C. as it was discovered that an arrowhead had been lodged in his left shoulder, and whose remains have been well preserved in a glacier between Italy and Austria. On the axe of Ötzi revealed to be made of copper and wood, details already investigated by Artioli, "It was then possible to date the axe to 3200 BC by using the radiocarbon method on the wooden handle. We then identified the area from which the copper of the blade came, and discovered it to be Tuscany. "

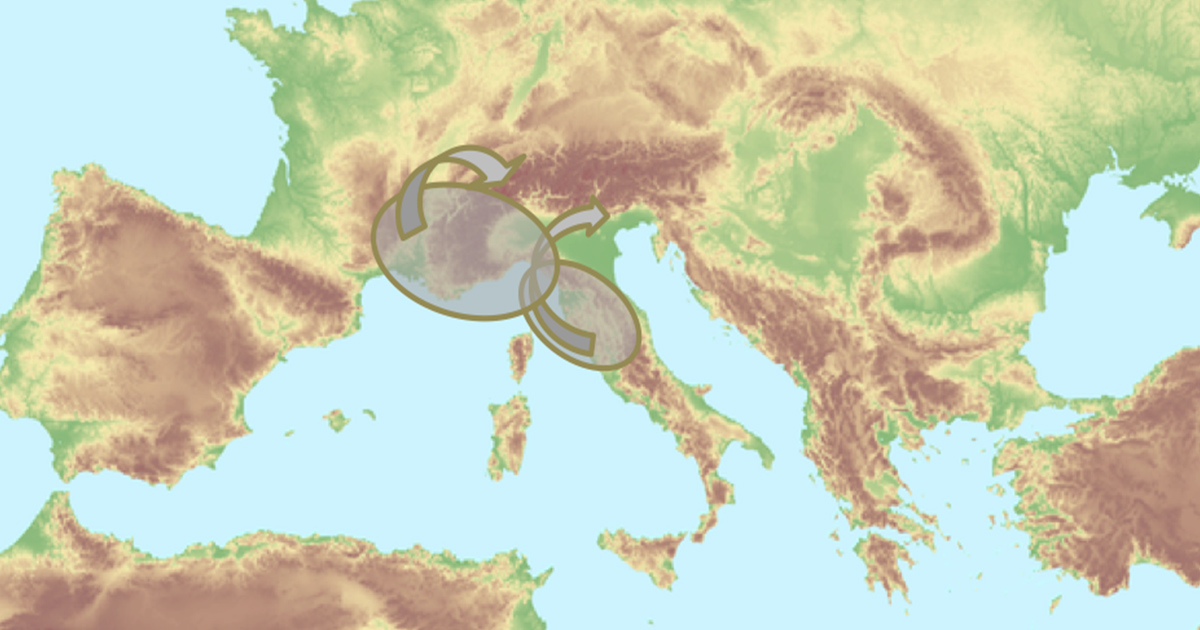

Therefore, 3,000 years ago Italy had already been a well-developed metallurgy. The new finding of Artioli and his team adds a new piece to this puzzle. "As expected, most of the objects examined were built with copper extracted in Tuscany" Artioli continues, "but some objects, which is unsurprising, were forged with copper from the western Alps or that from the southern part of the Massif Central of France. This is a sign that there had already been a Tyrrhenian circuit of exchange and trade in this fairly newly developed metal. We also know that the rich deposits of the South-Eastern Alps were not well exploited during this period, even if they represent the greatest source of metal from the second half of the 3rd millennium and throughout the Bronze Age."

The study confirms the importance of the rich mineral deposits of Tuscany as a source of copper for the Endolithic communities in Italy, but with traces of new trade and import routes that began and ended across the Alps. A thousand years before the Bronze Age, in pre-historic Europe, there had already been a well-developed exchange network. "Before our studies, there was no such data, it was thought that all copper came from the East or the Balkans, including that of Ötzi's axe. Instead, we now have a much clearer picture of the metallurgy of this period, in which understanding the journey of Tuscan copper and the Tyrrhenian has become

Tuscan copper reached the Alps, at least as far as the Austrian border, while French copper reached central Italy. How the exchange actually took place will be the task of archaeologists to rebuild it. Leaving to new studies which could reveal new trade routes or new deposits a better understanding of the diffusion of copper networks.