Ukraine's critical minerals between politics, economy, and science

Rare earth oxides (© Peggy Greb/US Department of Agriculture).

After months of negotiations, at times very tense, on April 30 the United States and Ukraine signed an agreement on critical minerals, which, according to the US Treasury Department, will also help the country’s reconstruction after the conflict. American President Trump had long maintained that such an agreement was a condition for providing future security guarantees to Kyiv, while Ukraine continues to resist the full-scale invasion by Russia. The agreement provides for the creation of a joint investment fund between the United States and Ukraine to explore mineral resources and, although the details are not yet public, it should establish a fair distribution of the revenues generated.

Ukrainian Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Economy Yulia Svyrydenko (who flew to Washington to sign the agreement with US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent) stated in a post on X that the new fund “will attract global investments to our country.” In fact, the agreement should concern projects in the mining, oil, and gas sectors; but the partnership must first be ratified by the Ukrainian parliament. In return, the United States is expected to provide new aid to Kyiv.

The announcement of the signing came just a few days after a meeting between Presidents Donald Trump and Volodymyr Zelensky on the sidelines of Pope Francis’s funeral, captured in a photo that quickly went viral. The original agreement was supposed to be signed in February, but it sensationally fell through after a joint press conference at the White House, where the tone was anything but calm.

Trump and Zelensky in St. Peter’s basilica (© The Presidential Office of Ukraine).

The treasures beneath Ukrainian soil

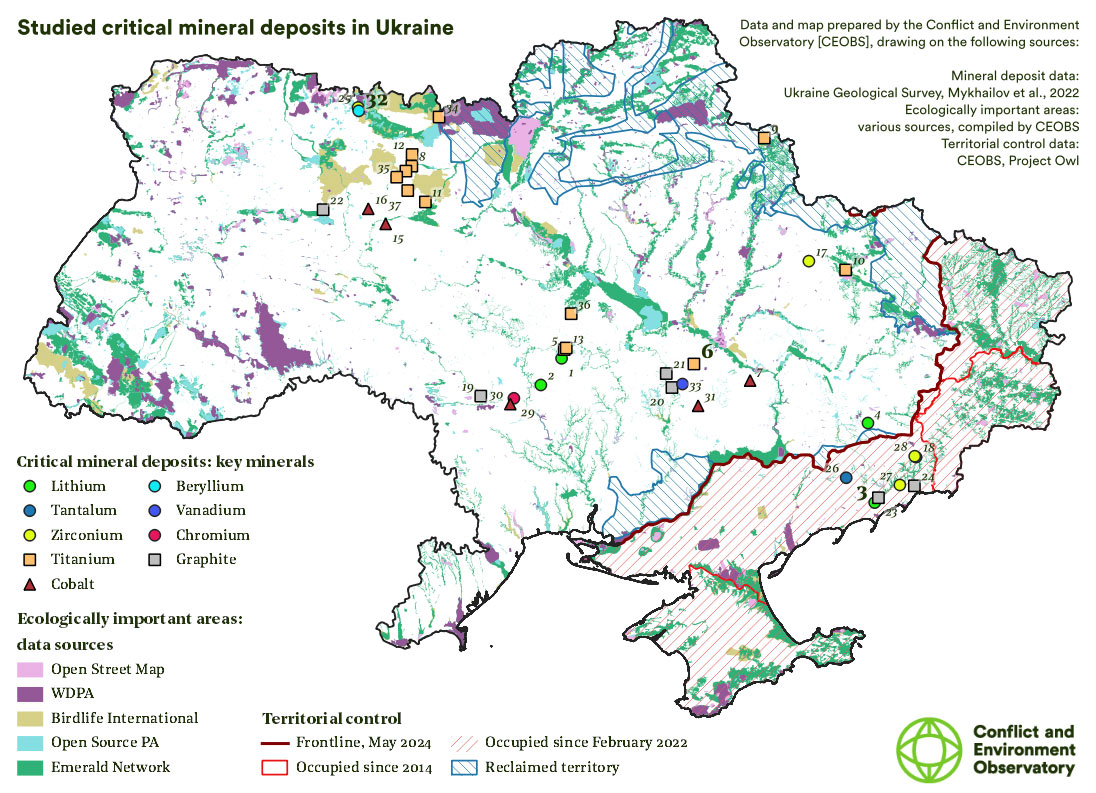

Ukrainian territory possesses vast reserves of critical minerals such as graphite, titanium, and lithium, which are in high demand for their use in renewable energy, military applications, and industrial infrastructure. US interest in these resources comes in the context of a growing trade conflict with China, which currently controls almost 90% of the world’s rare earths.

But what is special about Ukraine’s critical minerals (which include more than just rare earths), and why are they at the center of international negotiations? To understand the importance of these elements, we spoke with Volodymyr Pavlyshyn, professor at the Institute of Geochemistry, Mineralogy, and Ore Formation of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. He tells us that “land and mineral resources are the two most important factors that can most effectively influence the development of Ukraine’s economy now and in the near future. This is because, Until 2014, Ukraine had approximately 25% of the world’s black soil (chornozem), and it is also one of the richest countries in Europe in terms of mineral resources”.

Among the various Ukrainian minerals, there are some that are of particular interest to politics -Pavlyshyn continues- “rare earth metals, lithium, and titanium; they differ in their properties, but almost all are widely used in the development of modern electronics”. These metals are mainly found in a unique geological structure called the Ukrainian Shield, a wide band that covers approximately two-thirds of the country’s territory, stretching from the northwest to the southeast. The mineralogist explains that “the Shield consists of hard rocks and is surrounded by softer formations (oil, coal, gas, sand, etc.), and there are several lithium deposits on the Ukrainian Shield. The most interesting are two deposits in the south of the Shield:the Polokhivske deposit, currently the richest, and the Shevchenkivske deposit, which is practically ready for exploitation but is currently conserved”. The latter deposit is particularly problematic because it is located in the Donbas, one of the areas occupied by Russian forces.

Map of critical minerals in Ukraine (© Conflict and Environment Observatory).

From the Soviet Union to today

The extraction of critical minerals often involves environmental risks, especially in a country that has suffered significant industrial damage due to the war. For this reason, we asked Pavlyshyn how he thinks Ukraine can ensure sustainable mining practices. He replied that it is worth turning to history: “The Soviet Union exploited Ukrainian resources in a predatory manner: while lithium extraction was small, Ukrainian titanium accounted for more than 70% of the USSR’s total supply; mercury and certain kaolin clays had approximately the same percentage. The USSR did not develop green technologies, but instead ramped up extraction: this led to the situation where, in 1991, Ukraine accounted for 5% of the world’s mineral extraction while occupying less than 1% of the Earth’s land area. This was mostly the result of the exploitative extraction of natural resources”.

Today, however, a broad range of efficient methods for extracting, processing, and consuming minerals should be applied. And the issue -according to the Ukrainian professor- can be divided into two parts: “the first one is extraction, and the second one is the environmental component. The most important issue that needs to be addressed is profitability. And in order to calculate profitability, one must take into account a multitude of details, including mineral composition, temperature, and the evaporation of harmful gases”.

To solve these problems, Pavlyshyn argues that “it is important to transition our technologies to biological and physical methods. Before 2014, when Russia first invaded Ukraine, there were small attempts to do this. But those were startups, still operating at the laboratory level (mostly in Kryvyi Rih, Dnipro, and Zaporizhzhia); biotechnologies were not in use at large industrial facilities. Currently, there are some areas of environmentally focused development in the mineral resource sector where we are hopelessly behind and cannot produce our own technologies, and instead must adopt international innovations”. For example, the mineralogist cites Japan, where there are “technologies for developing deposits that extract not only the main valuable component but also accompanying trace elements, which can be just as valuable. In contrast, in Ukraine, only the main component is extracted, and there are no technologies capable of recovering those trace elements”.

A 1921 poster reads “Donbas is the heart of Russia” in reference the strategic importance of its mines.

Science between war and peace

Given the recent signing of the agreement with the United States, we asked Volodymyr Pavlyshyn how Ukraine could use this partnership to restart the economy while maintaining sovereignty over its critical assets. He replied that it is a very important issue since “it is new for Ukraine, and therefore, I believe that even at the highest levels of government, it has not yet been fully developed. For example, there is a simple formula: ‘50/50’: hypothetically, if 10 tons of cerium are extracted, they are split evenly (5 tons go to the US, and 5 tons remain in Ukraine). This is a very primitive, schematic approach. Nevertheless, proper agreements must be thoroughly developed so that this cooperation brings benefits to the economy without harming the environment”.

The situation in Ukraine is indeed very complex and, as the mineralogist concludes, “there are many questions regarding the deposits that are currently under occupation”. For this reason too, the agreement that will bring US economic interests to Ukrainian soil has been viewed positively, although negotiations to end hostilities still seem far off.

We were able to interview Professor Pavlyshyn thanks to the help of Science at Risk, the digital platform and community of Ukrainian scientists that helps journalists, donors, and foreign researchers establish contacts with specialists in Ukraine. Their mission is to report how Ukrainian research institutions and scientists are facing the challenges posed by the war: for example, according to their data, 15% of Ukrainian scientific infrastructure has been damaged due to the full-scale invasion by Russia. Nevertheless, 88.2% of scientists have remained in Ukraine, but 72.9% of them report being unable to continue their research at the same level as before. For science as well, therefore, a just and lasting peace is the crucial goal to achieve, and it is hoped that the newly signed agreement is a step in this direction.