#Perunaltracostituente. Women’s voices go unheard during the pandemic

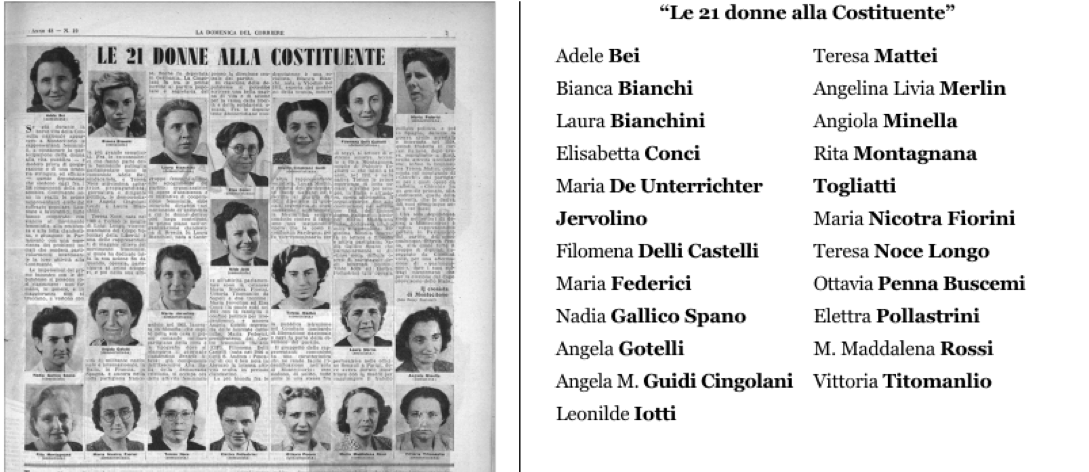

Some of them came from the resistance struggle against fascism, others from social work, others from activism in political parties, still others from teaching in schools: they were the 21 Italian women elected in the universal suffrage of June 2, 1946, which brought women to Parliament for the first time. On that occasion, people voted for the institutional referendum that would decide between the Monarchy and the Republic, and for the Constituent Assembly. Those 21 deputies, who today seem to us a small number when compared to the 556 elected, marked the entry of women into the highest level of our representative institutions and into the debate that led to the drafting of our constitutional charter. A momentous passage. We owe them gratitude because, despite coming from different experiences and from different political positions, they made common cause around the themes of female emancipation, to which their attention was mainly devoted. Senate member Lina Merlin, a graduate in French language and literature from the University of Padua, made a decisive contribution to the writing of Article 3 of the Constitution, which concerns the equality of all citizens. She was responsible for adding the words "without distinction of sex" to the body of the text:

All citizens have equal dignity and are equal before the law, without distinction of sex, race, language, religion, political opinions, personal and social conditions.

74 years have passed since that historic moment that allowed the Italian state to become a democracy. The position of women in the social, cultural and political fabric of the country has since taken root and widened: from 1946 onwards women have been able to study, work, do politics, take to the streets in the topical phase of what we now call 'historical feminism', and claim rights and presence in the body of the nation. We have entered the sectors of industrial production, business, economics, and academic, state and governmental institutions, with determination and competence. But we have all experienced and continue to experience, today in a clear way, the hardness and coldness of that glass ceiling that prevents the majority of competent and far-sighted people from accessing top positions where decisions are made that affect everyone's life. One wonders how it could have happened, after such a far-sighted beginning in 1946.

I do not intend to provide complex analyses of what forces us, in 2020, to still be here to claim the right to be heard. I am more interested in intervening on what awaits us, on what the challenges that women and society may all face after suffering the unexpected and spectacular attack of a virus that has put us in front of our human, social and environmental fragility. We are now emerging, prudent and hesitant, from a lockdown that has affected the very fabric of our country, reshuffled its priorities, and re-opened the question of freedom and access to rights.

In this context, the voice and experience of women, who represent the majority of those who 'served' the country in the Covid19 emergency, remains unheeded, despite the manifestations of gratitude for those who have taken care of the victims of the pandemic. But I wish to argue that, if women’s caring abilities are now widely acknowledged, then now is the time for women to finally "take care" of the country, to transform it deeply, outlining scenarios, defining priorities, making decisions, and speaking on the public scene. In the face of the proliferation of all-male emergency task forces, made up of men in leadership positions that have always been denied to women, we think that the times are more than ripe for another thought and another way of offering skills, vision and a future.

The women of 1946 had come out of war and resistance to Nazi-fascism. We have experienced a long period of peace and prosperity also thanks to them, but we have stumbled upon an unexpected and disruptive development of the planetary ecosystem that has put us in check and is asking us to rethink what it means now to guarantee health, survival, and equal rights. These priorities must be supported by the vision and collaboration of all, and particularly of women, without whose experience this planet will not survive.

In the last few weeks, voices have finally risen (see interventions on La27ora, articles in the Corriere della Sera, #datecivoce, the appeal of the United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres), which express strong concern about the heightening of inequalities, discrimination and violence due to the pandemic, and ask to give women adequate voice and representation in decision-making places for a new beginning.

My invitation, for those who believe it is right to strive to affirm life, decent work, equal participation in the economy, in society and in politics, with particular attention to the generations that come after us, is to look back at our history, which will not be able to tell us how to avoid the mistakes of the past but can surely make us understand where we have gone wrong, and cultivate a critical perspective that will redirect our gaze and produce new paradigms of public life, including a supranational (hopefully 'planetary') perspective, and a new grammar of relations between women and men.

One way to begin this far from simple work is to put together reflections, ideas, experiences and good practices, which may produce a pro-active critical vision for our communities and governmental institutions, as a contribution to the times that come. In this 'constituent' phase, it is crucial to identify concrete proposals, starting from actions and initiatives that we could / should bring to the university, in an uninterrupted dialogue with realities outside the academy.

Thanks to everyone who wants to get involved in the public space of #perunALTRAcostituente in the Bo Live magazine of the University of Padua.