IPCC: The impacts of climate change on human settlements

Pakistan Humanitarian Aid Flood Relief, 13 September 2010

Over 1000 people have lost their lives in Pakistan due to floods that have devastated nearly half of the country. Over 30 million people, roughly 15% of the country’s population, have been hit by the flooding, and they had already faced a similar disaster in 2010-2011. Around 500,000 homes have been destroyed, and the Minister for Climate Change, Sherry Rehman, has described it as the worst humanitarian disaster of the past decade.

From mid-June, Pakistan has been facing exceptionally intense monsoon rains, that have caused landslides and floods. From the beginning of August, an area the size of Northwestern Italy has been submerged. The Prime Minister Sharif announced a relief package of 10 billion rupees (45 million dollars) for the hardest-hit province, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, with each affected family receiving 25,000 rupees, equivalent to just 112$.

Pakistan is responsible for less than 1 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions and yet it is among the top 10 most vulnerable countries to climate change pic.twitter.com/ad8vKsnvXi

— Vanessa Nakate (@vanessa_vash) August 29, 2022

Risks and opportunities for action

According to the IPCC Report published in February, 2022, cities and settlements are key players for implementing urgent climate prevention measures. Here, the concentration and interconnection of people, infrastructure, and resources in both urban and rural areas create both risks and solutions.

On a global level, urban population has grown by nearly 400 million people from 2015 to 2020, with over 90% of this growth occurring in less developed regions. The fastest growth took place in unplanned settlements as well as in small to medium-sized cities in low- to middle-income countries. This has led to increased vulnerabilities, as their capacity to adapt to a changing climate is limited.

The worst impacts

Flooding caused by heavy rainfall is not the only threat that climate change poses to settlements. Exposure to climate impacts such as heatwaves, urban heat islands, and extreme precipitation, combined with swift urbanization and a lack of climate planning, disproportionately affects marginalized urban populations and key infrastructure needed to counter climate change.

Even Covid-19 has had a significant impact, increasing vulnerability to climate change in urban areas. The effects on health, liveability, and well-being are particularly pronounced among socially and economically marginalized groups.

Urban areas and the related infrastructure are susceptible to both cascading and cumulative risks that arise from the interaction between extreme weather events and increasing urbanization. Drought, for instance, affects food production in rural areas, which in turn threatens urban food security.

Coastal cities

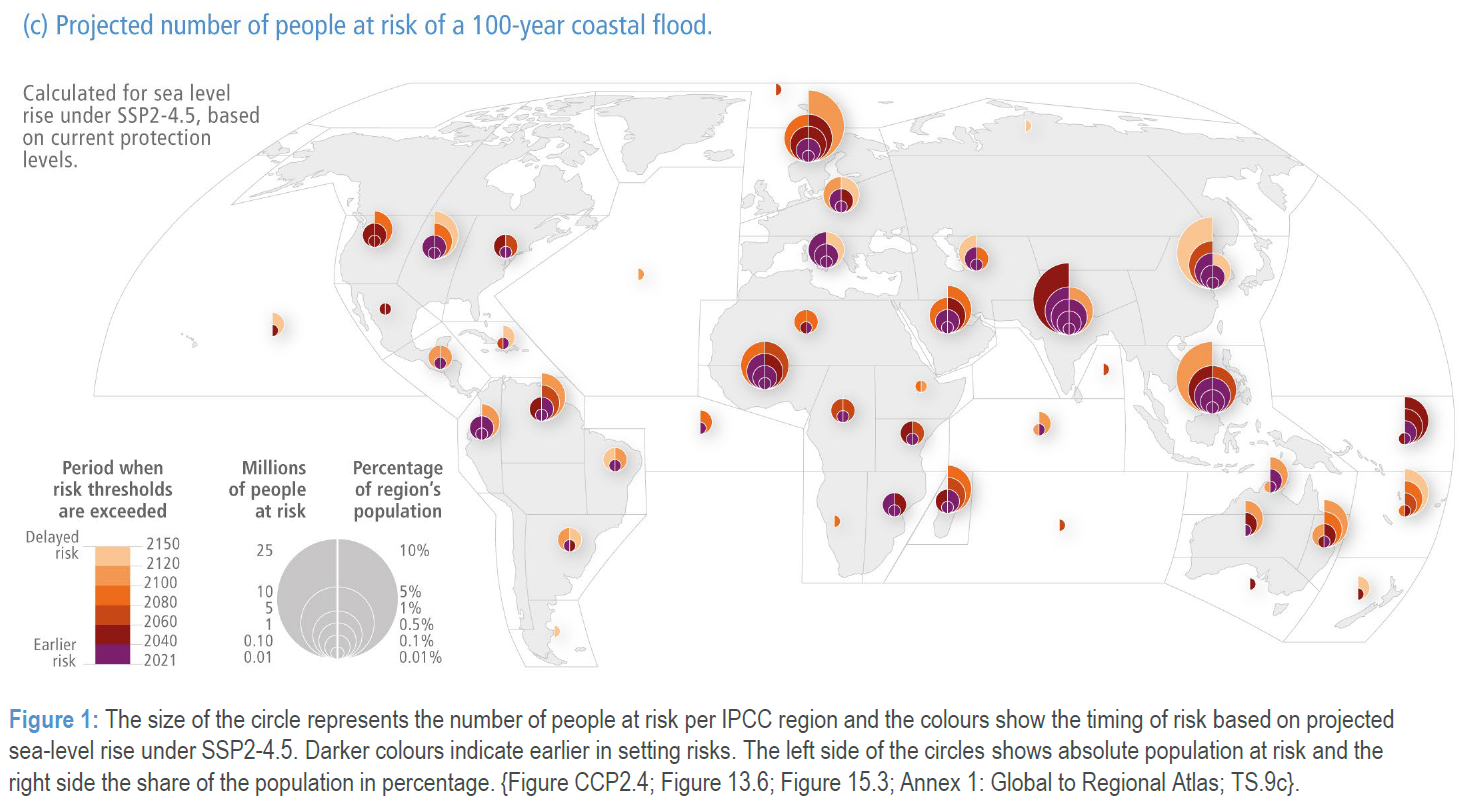

Coastal cities are more severely affected than other areas, due to the exposure of many of their assets, economic activities, and large parts of the population. People are already suffering the impacts of increasing sea level rise, such as coastal subsidence, flooding from high tides, salinization of groundwater, shifts in ecosystems and agriculture, and damage from flooding and coastal erosion. Coastal settlements characterised by poor urban planning and with high levels of inequalities, as well as cities on deltas subject to subsidence and small island communities, are particularly vulnerable.

Projections anticipate that risks to coastal cities and settlements will increase by at least one order of magnitude by 2100 without adequate mitigation and adaptation measures. The population exposed to flooding risks in coastal areas will rise by 20% if the average sea level rise increases by 0.15 metres compared to today; it will double with a 0.75 m rise; and it will triple with a 1.4 m increase.

Climate-resilient development hinges on how effectively coastal cities and settlements can implement adaptation measures and urgently mitigate greenhouse gas emissions.

Rapporto IPCC febbraio 2022, AR6 WG2, Human Settlments fact sheet

Adaptation plans, opportunities, and gaps

Several cities and settlements have already developed adaptation plans, but few have implemented them. Current adaptation measures exhibit gaps, leading to vulnerabilities to climate change across all regions of the world.

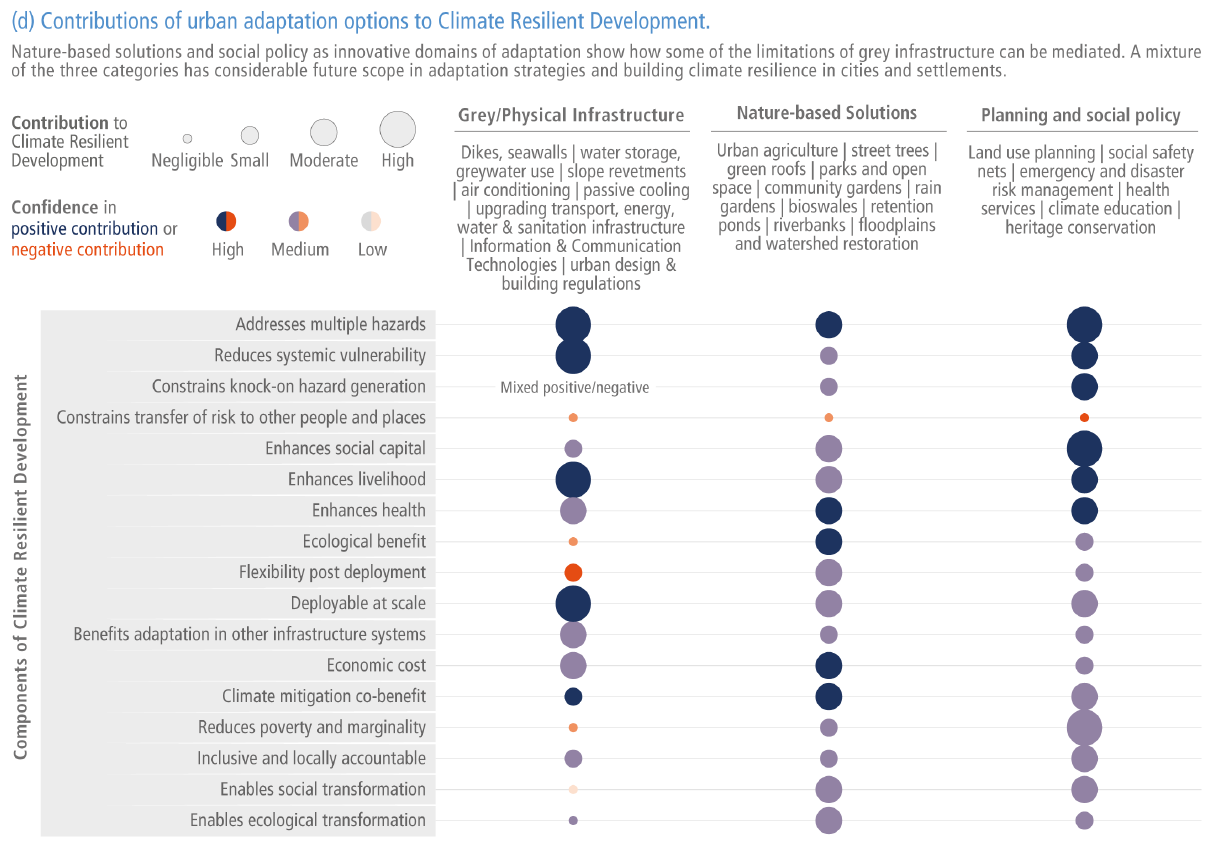

The rapid and ongoing growth of urban populations and the unmet need for decent, affordable, and healthy housing and infrastructure, presents a global opportunity to integrate inclusive adaptation strategies and development. The restoration, optimization, and redesign of existing infrastructure, together with the planning of new urban areas, can combine already existing policies with nature-based solutions to create inclusive adaptation processes.

Among the interventions that reduce climate vulnerability are discouraging development of high-risk areas, using coastal wetlands or marine barriers for protection, adopting elevated housing above sea level, and managing population relocation from coastal areas.

IPCC suggests focusing on economic and ecological feasibility of green infrastructure, restore ecosystem services, and sustainably manage urban water resources.

Unfortunately, cases of maladaptation have already been observed due to inadequate knowledge, shortsighted political actions, fragmented and sector-specific approaches that lack inclusivity. These include inflexible infrastructure that cannot be easily repurposed, and populations that cannot be relocated from vulnerable areas. Long-term planning is essential to avoid such situations.

Urban adaptation can promote social capital, liveability, human and planetary health, and contribute to a low-emission future. Participatory planning of infrastructure and risk management in underserved and precarious areas, consideration of indigenous and local knowledge, and efforts to build local governance systems or leaderships, are all examples of inclusive approaches that generate shared benefits and equality.

Rapporto IPCC febbraio 2022, AR6 WG2, Human settlments fact sheet

Global urbanization: a window of opportunity

By 2050, an additional 2.5 billion people are expected to live in urban areas. The way these settlements and their key infrastructure are designed and maintained will determine the level of exposure and physical and social vulnerability, as well as the capacity for resilience to the impacts of climate change.

Governance and finance

Unfortunately, the available innovations in adaptation strategies, social policies, and nature-based solutions have not been matched by innovations in adaptation financing, the IPCC emphasizes.

The financial sector has generally favoured the wealthy over the poor, prioritized large large engineering projects over maintenance and social innovation, privileged grey infrastructure over green or blue ones. Access to financing is more complicated for cities, local or non-state actors, and contexts where governance systems are fragile.

A governance committed to climate action is most effective when it ensures the participation of all stakeholders, from the local to the global level. This includes contributions from individual households, communities, the private sector, and non-governmental organizations, as well as the involvement of indigenous peoples, religious groups, and social movements.

This article was translated into English by Sofia Belardinelli. The original version of this article is available here.

ALSO READ:

- IPCC: Nearly direct correlation between emissions and global warming

- IPCC: Impacts of climate change are not equal for everyone

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Africa

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Europe

- IPCC: The impact of climate change on small islands

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Asia

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Oceania

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Central and South America

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on North America

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on human settlements

- IPCC Synthesis Report: every fraction of a degree matters