Mansoor’s Orange Clothes: The Story of a Guantánamo Survivor

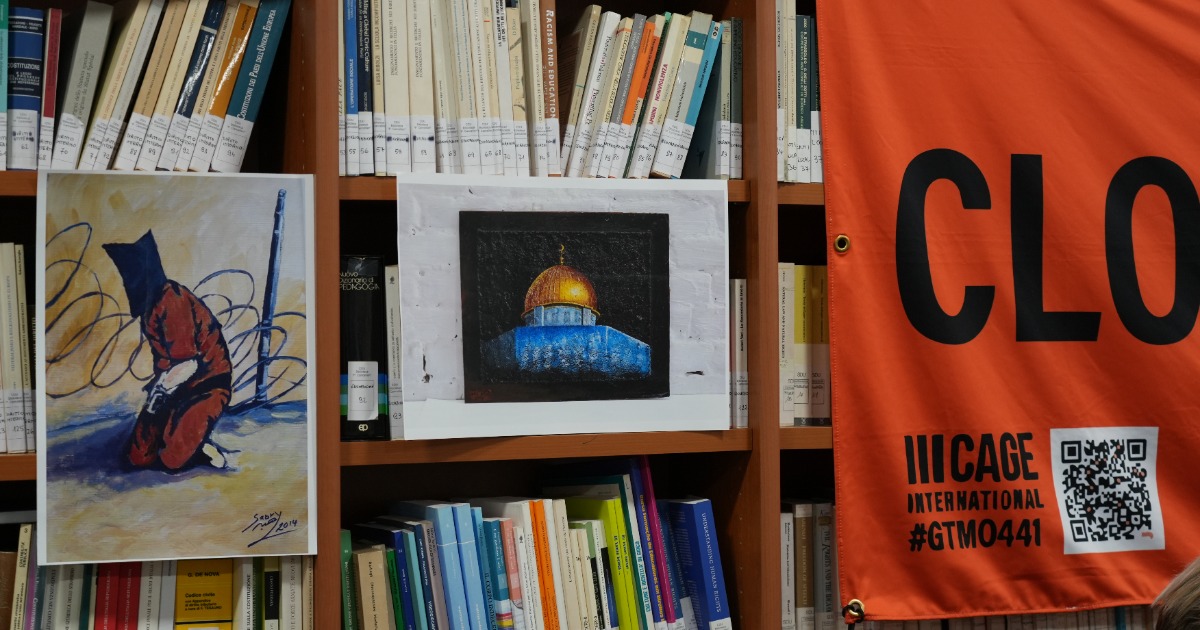

Mansoor Adayfi at the Human Rights Centre, University of Padova

“Which newspaper do you write for?” he asks smiling. “Do you know you’re the first Italian to interview a former Guantánamo detainee?”

Mansoor Adayfi is disarmingly warm, generous with his time, even playful. He talks easily, with pleasure, as if speaking itself were an affirmation. He is in Padua to present his memoir, Don’t Forget Us Here (Hachette, 2021), in which he recounts the 14 years he spent in Camp X-Ray at Guantánamo Bay, without charge or trial. The event is promoted by Advocacy Hub – Students’ Voices at the Human Rights Centre.

Then there is the orange. An orange T-shirt, orange socks and a jacket — the color he was forced to wear as a detainee, now universally associated with Guantánamo and its suspension of rights. It remains a color heavy with stigma. Adayfi wears it deliberately. What once marked humiliation has become an emblem of pride and agency — the visible grammar of his activism.

What is most striking is the contrast between what he describes and how he does so. He is open, affable, quick to joke and rarely becomes emotional. At times he seems almost removed from the trauma itself, as if the ghosts one might expect do not dominate the room. There is no rhetoric of suffering, no performance of pain.

“I wasn’t the strongest,” he says. “I wasn’t the toughest. Maybe I was the most open.” He was never shy, he explains, and that openness — more than endurance — kept him from losing his mind. Talking, connecting, refusing isolation became a way to survive.

In reclaiming the color orange, Adayfi has done something similar with his story: turning a symbol meant to erase individuality into a declaration of presence, memory, and resistance.

A Life Before — and the Road to Afghanistan

Long before Guantánamo, says Adayfi, there was an ordinary life in a little village in Yemen, shaped by family and education. Finishing high school marked a turning point: “I could see how happy my mother was, my father, my sister,” he says.

The question he says he has been asked ever since — What were you doing in Afghanistan, and why? — is one he no longer avoids. “It’s a legitimate question,” Adayfi says. “Because people always say: you must have done something wrong.” He pauses. “That’s how stigma works. Some people punish you for 14 years, others for the rest of your life.”

To understand his presence in Afghanistan, he argues, it is necessary to rewind history — before Guantánamo, before September 11. He traces the shifting alliances of the 1980s and 1990s, when the United States supported the Afghan mujahideen against the Soviet Union. “They were called freedom fighters,” he notes. “They were welcomed at the White House. Then yesterday’s allies became today’s enemies.”

Adayfi was in Yemen at the time, studying and working at an institute that had been asked by the Yemeni government to research the rise of Al Qaeda and its ideology. “There was no Google, no social media,” he says. “If you wanted to write seriously, you had to go physically. You needed facts.”

“I was the guy who carried the bags,” he insists. His task was to assist a senior scholar with field research — interviews, observation, documentation — into how extremist ideology was being constructed and justified. “To critique it,” he says, “you have to understand their arguments, especially from a religious perspective.”

The journey itself was precarious. Pakistan, then Afghanistan, coordination with governments, permission from the Taliban, interrogations along the way. “It wasn’t easy,” he says. “We were questioned by everyone — the Taliban, Al-Qaeda. Our passports were confiscated. We were searched. Constantly.”

“ Reclaiming the orange uniform once imposed on him, Mansoor Adayfi turns stigma into a language of memory, activism, and warning for the present

Their local contact point, he would later discover, was a Saudi charity — which he came to understand only years later, in Guantánamo, as a front for Saudi intelligence.

After September 11, everything accelerated. They were told to leave Afghanistan as quickly as possible. On the way, they were asked to help transport humanitarian supplies — medicine, blankets, food. At a checkpoint, the car was seized. Then came another handover, and another.

“At that point,” Adayfi says, “the CIA had started buying loyalties.” Leaflets were dropped promising rewards: “If you bring an Arab, you get money.” So — his word — he was sold to American forces by the men of General Dostum, a powerful warlord. “Like many others,” he says. “That’s how I ended up there.”

Of the roughly 780 men and boys detained at Guantánamo, Adayfi notes, only about five percent were captured directly by U.S. forces. “The rest,” he says, “were sold.”

For three months he was held in a CIA “black site,” part of the global network of secret prisons where detainees were disappeared, tortured, sometimes killed. What happened there, he says, was unspeakable — and incomparable even to the 14 years that followed. “The black sites,” he says, “were designed to break you before you even arrived.”

How Mansoor Survived Guantánamo — and How He Finally Left

Survival at Guantánamo, Adayfi says, wasn’t about physical strength. It was about refusing erasure. What saved him, he insists, was not submission but resistance — quiet at first, then collective.

When he arrived in Guantánamo, he encountered “an ocean of orange”: shaved heads, shackles, cages exposed to sun and rain. Facts no longer mattered: proofs were classified and ignored, while the label itself became the verdict. It was not, he says, a prison but a black hole, designed not to establish truth but to make legal accountability disappear.

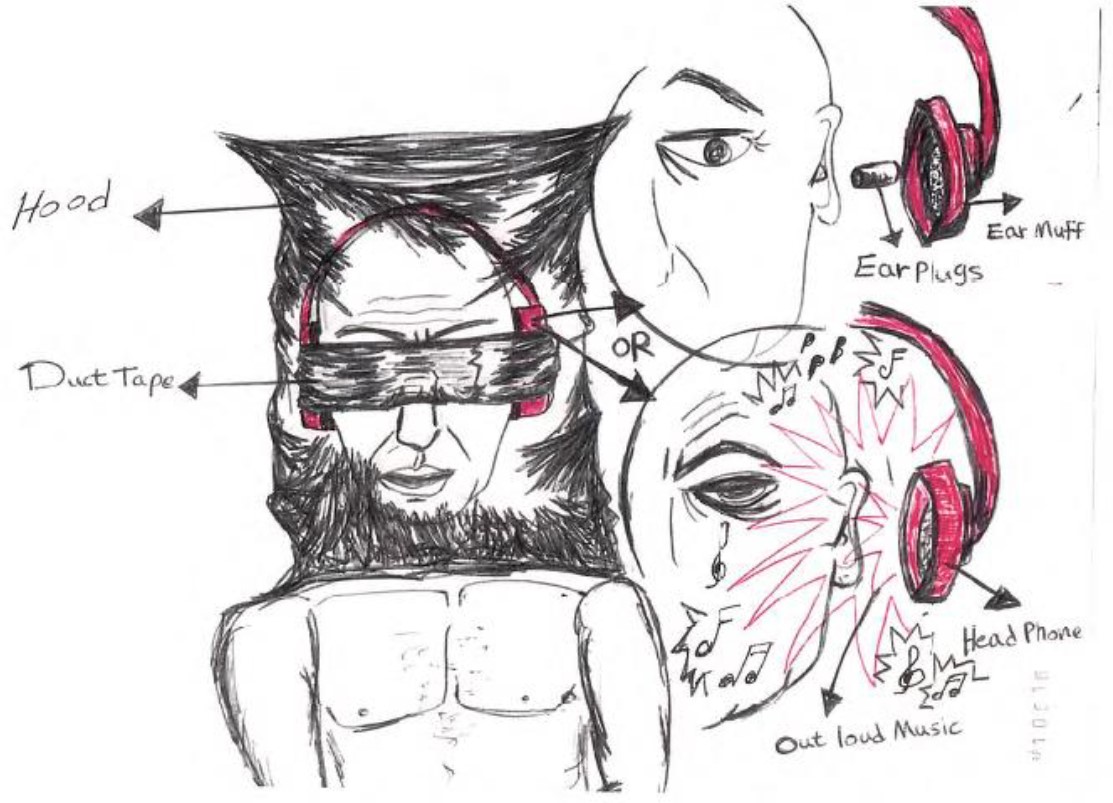

Everything that defined him was systematically stripped away: his clothes, his hair, his name, replaced by 441, his personal detainee number. He was shackled, hooded, beaten during what the military called “processing”. The first camp was a row of wire cages under the Caribbean sun, exposed to heat, rain and constant interrogation. No charges, no lawyers, no timeline: “Guantánamo was outside the law,” he says. “Even calling it a prison is wrong, because prison implies a system. There was no system.”

Detainees were told they had no rights: the Geneva Conventions did not apply, American and international law did not apply. They were labeled “the worst of the worst.”

Abu Zubaydah © 2021 Licensed by Mark Denbeaux, Professor of Law at Seton Hall Law School and Chantell M. Higgins

“My childhood saved me,” Adayfi says. The same curiosity and openness that once got him into harmless trouble now kept him alive. He talked. He connected. He refused to internalize the silence that the camp imposed. When guards ordered detainees not to speak, not to look up, not even to pray together, doing so became an act of defiance.

Resistance took many forms. Hunger strikes were one. Adayfi himself endured force-feeding, strapped to a chair as thick tubes were pushed through his nose. “The pain of hunger,” he says, “was easier than the pain of humiliation.”

But resistance was also cultural, emotional, human. Men from more than 50 countries, speaking over 20 languages, began to build a shared life from nothing. They taught each other. A doctor gave lessons, a teacher explained grammar, someone described how to cook dishes they would never taste again. They sang — in Arabic, Pashto, Urdu, Persian, even German — voices rising together at night until the sound filled the blocks. Guards panicked. Helicopters hovered. The singing continued.

Art, when it was finally allowed, became another lifeline. With plastic spoons, apple stems, scraps of Styrofoam, detainees carved hearts, flowers, moons. Poems were written on toilet paper. Paintings — often of trees, skies, oceans — recreated what solitary confinement had taken away. “Art,” Adayfi says, “connected us to our memories. To the parts of ourselves they couldn’t reach.”

The authorities understood the danger. Creativity was confiscated, classified, treated as subversion. A simple poem once triggered a full emergency lockdown. Still, the men persisted. “We took nothing,” Adayfi says, “and made something. What is more human than that?”

Over time, Adayfi learned another form of survival: education. After years trapped in cycles of fear and rage, he made a decision. “I didn’t want hatred to be my identity,” he says. He began studying obsessively — law, language, history. He taught himself English, spending up to ten hours a day reading, listening, writing. Words became tools. Later, they would become weapons.

In 2010, after nearly a decade of isolation, detainees were suddenly allowed communal living. It was not freedom, but it was change. Negotiations — unthinkable before — began. Conditions improved: books, newspapers, phone calls, televisions. Adayfi helped organize dialogue with camp authorities, insisting that improvements apply to everyone, not just a few. “We learned how power works,” he says. “And how to push it.”

He began writing his story as legal correspondence, letters smuggled out through lawyers. The first drafts were confiscated by the FBI. He rewrote them. Eventually, those letters would become Don’t Forget Us Here, a memoir published after his release, bearing witness not only to abuse but to solidarity.

Released but not free

Adayfi was finally cleared for release — like most detainees — long before he was allowed to leave. Freedom came slowly, bureaucratically, without apology. When he walked out of Guantánamo in 2016, he carried no compensation, no formal exoneration. Only memory.

But freedom, when it finally came, did not mean going home. After his release, Adayfi was not allowed to return to Yemen. Instead, he was resettled in Belgrade, thousands of miles from his family. Today, seeing his parents remains difficult, mediated by borders and bureaucracy. Liberation, he explains, came with its own form of exile.

However, in Serbia, he rebuilt himself piece by piece. He studied. He earned a degree in management. And slowly, deliberately, he transformed survival into purpose. Today, Adayfi is one of the most visible former detainees campaigning for the closure of Guantánamo, and for the dismantling of all systems of indefinite detention without charge or trial — wherever they exist, under whatever flag.

He speaks not as a victim but as a witness, issuing a warning. Guantánamo, he says, was never just a prison. It was a blueprint — for indefinite detention, for legalized exception, for a world in which labeling someone a “terrorist” suspends their humanity.

“What happened to us,” he says, “can happen anywhere.” And in many ways, he argues, it already is.

This, too, is why he wrote Don’t Forget Us Here. Not simply to recount what was done to him, but to insist that Guantánamo is not an anomaly safely locked in the past. It is a model — one that can be replicated, exported, normalized.

The orange he wears is no longer a uniform imposed by force. It is a warning. And a reminder.

Forget Guantánamo, he suggests, and it will happen again.