SOCIETÀ

Back to the future. The human society as an organism

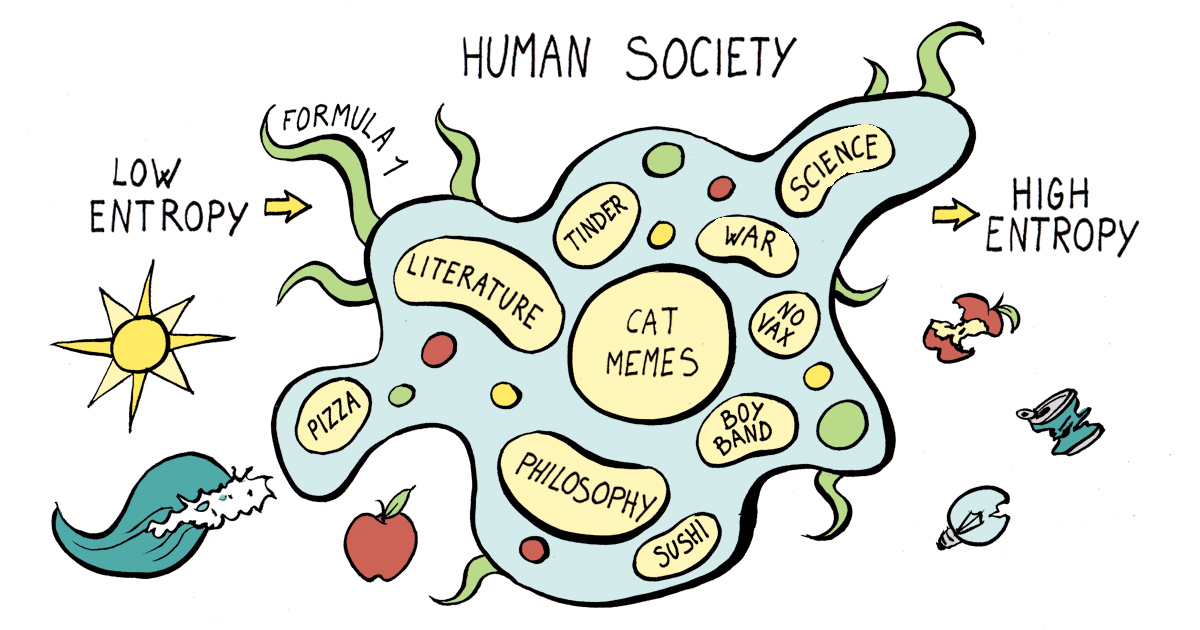

Cartoon created by Lorenza Luzzati

A living organism evolves, adapts, interacts with its environment, reproduces. A living organism is, in a sense, an individual, yet it is not entirely autonomous, acting in complete isolation from its surrounding environment. In fact, any living organism is embedded in an environmental context, which is the conditio sine qua non for its very existence. Furthermore, the environment itself is continually moulded and changed by the complex of relationships formed by the living beings inhabiting it.

According to many ecological economists, the properties of a living organism can also apply to human societies. Indeed, like any organism, socioeconomic systems have their own metabolism: as part of a closed system (the biosphere), they exchange matter and energy with it. More precisely, societies are at a constant state far from equilibrium, and in order to survive and reproduce, they must establish a flow of exchange with the surrounding environment from which they take low entropy matter and energy, i.e., low-cost and easily available for human activities, and return high entropy waste to it, carrying out an irreversible transformation process.

This view of socio-economic systems clashes with the most widespread economic narrative, which presents the economy as a closed sphere with no ties to the outside world, without taking into account, for example, the material basis required for an economic system to function. Following the teachings of Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, ecological economics recognises that the social and economic spheres belong to the broader natural dimension, and grounds its theory in the laws of thermodynamics and biology, from which human reality cannot escape.

«The question is whether the comparison between societies and biological entities can be fully carried through», says Mario Giampietro, one of the founders of ecological economics, now ICREA professor (Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies) at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. «We could characterise societies as ‘metabolic repair systems’, able to adapt and reproduce, and composed of different elements that interact with each other and contribute to the maintenance of the system. Each of these elements – which might be compared to the organs of a body – serves a precise function, and they are all organised into a hierarchical system that ensures the functionality of the whole. The primary dimension for these ‘organs’ is not the individual, but the community: they require an ecosystem for their very existence, as they are dissipative structures that exchange resources and waste with their surroundings. Viewed from this perspective, even human societies acquire a new significance: the parts and the whole are equally important, albeit in different ways, and it is necessary for the system to remain in a state far from equilibrium in order to ensure their well-being. In fact, according to thermodynamics, any system which is in a state of perfect equilibrium (of maximum entropy) would be dead.

In this light, individuals find a new role and meaning within the community dimension. However, within human societies working for the common good, like cells in an organ or organs in a body, is not the whole story: the psychic life of individuals plays a central role for the functioning of a community. Moreover, 'individual' is a misnomer since each human being is itself a complex system, and not a homogeneous and indivisible unit, as assumed by the mainstream narrative.

«Unlike other living beings, human beings are reflexive: they have desires, passions, dreams and fears – what sociologist Niklas Luhmann called a ‘psychic structure’», Giampietro points out. «For a society to be functional, it is therefore essential for individuals to feel a connection between their own sense of identity and the identity of society; if this does not happen, cooperation fails, and the very social structure is at risk». By ignoring the importance of this non-rational dimension of human life, and describing society as merely based on free market and rational individualism, neoclassical economics provides a description of socio-economic systems that is completely detached from the real world».

Comics created by Lorenza Luzzati

Seeing society under a new light can thus open the possibility of challenging the soundness of the current mainstream economic paradigm, which is sometimes concealed even inside critical perspectives that do not really challenge it. Think of the concept of degrowth, for instance: as Giampietro points out, the term itself evokes the same semantic field employed by neoclassical economics, whereas what is needed today is an entirely renewed conceptual toolkit.

«By slightly changing our worldview, we can appreciate how the socioeconomic system aims not at producing goods and services, but rather at achieving those very ‘essentials’ that are needed for goods and services to even exist. In other words, society aims at ensuring the happiness of its members, to give them the opportunity to fulfil themselves, to guarantee fundamental rights in a benign environment. And, if we adopt this perspective, the purpose of the economy is not production per se, but mostly a caring attitude– towards other members of the community and towards the non-human world. Growth and degrowth, at this point, become redundant concepts, and lose their centrality and even their meaning».

If we recognise that thermodynamic laws are an essential element in the functioning of socioeconomic systems, we must conform to the limits they impose. This implies, for example, that the ‘circular economy’ and ‘sustainability’ are – at least in their current formulation – unfeasible paradigms, «A smokescreen used by proponents of capitalism to show that it should not really be overcome, and that the solutions for the problems of the present, which capitalism itself has nevertheless caused, can be found in it».

«What ecological economics suggests», Giampietro continues, «is that the only viable path passes through admitting that we live in a dissipative system that is irreversibly moving towards an increase in entropy, and that counteracting this trend has a high price in terms of energy and resources; that since the biosphere is a closed system, there are unsurmountable limits to economic growth, and no technological solution, no economic model can subvert these physical laws».

In such a complex system as the socio-economic one, a ‘hierarchy of complexity’ occurs – again recalling the analogy with biological systems. There two directions in which causality unfolds: top-down and bottom-up. In the first case, the emergent properties that determine the laws of the higher levels of complexity affect the ‘simpler’ components of the whole, in a cascade movement; in the second case, it is the characteristics of the structural elements of the whole that define a range of possible activities for the whole organism, on the basis of the physical and structural constraints of the individual components.

Complex entities – like societies – try to achieve a compromise between these two tendencies, to harmonise goals against physical constraints; human beings, on the other hand, have managed to bypass this need for compromise between goals (growth) and possibilities (the physical and thermodynamic constraints described above). «By importing, outsourcing production and disposing of waste, developed countries have been living well above their actual possibilities for decades; the living standards we are used to», Giampietro points out, «would be inconceivable if we had to compromise between the so-called ‘downward’ and ‘upward’ causalities. Staying true to our real possibilities – without recurring to tricks that, in the long run, turn out to be unsustainable anyway – is essentially a matter of responsibility, to which we called upon both as individuals and as a society».

The socio-economic system is an unusual organism undergoing continuous expansion (today, humans account for more than 30 per cent of the mammalian biomass), which has, over time, occupied the entire Earth system that hosts it. The analogy with living organisms is therefore not a mere metaphor, but instead provides theoretical and practical tools for pursuing an attempt to find internal and external harmony, and for delaying as much as possible the attainment of thermodynamic equilibrium.

ALSO READ:

- Back to the future. Georgescu-Roegen and the origins of ecological economics

- Back to the future. Human and non-human world, incommensurability of values

- Back to the future. The human society as an organism

- Back to the future. Prosperity, conviviality, sharing: For a gentle degrowth

- Back to the Future. Sustainable Development Goals and the sustainability framework: An open debate

- Back to the future. Sustainability is a political choice

- Back to the future. Environmentalism is a social issue

- Back to the future. Fuzzy, incomplete, plural: the world beyond hegemonies

- Back to the future. Actualizing the potential for socio-ecological change

- Back to the future. On waste pickers

- Back to the future. Implementing ecological economics: regional perspectives

- Back to the future. Valuing nature beyond money: from price tags to plural valuation languages

- Back to the future. The importance of complexity

- Back to the future. Healing our addiction to growth

- Back to the future. Herman Daly: the economy as a common good