Back to the future. Prosperity, conviviality, sharing: For a gentle degrowth

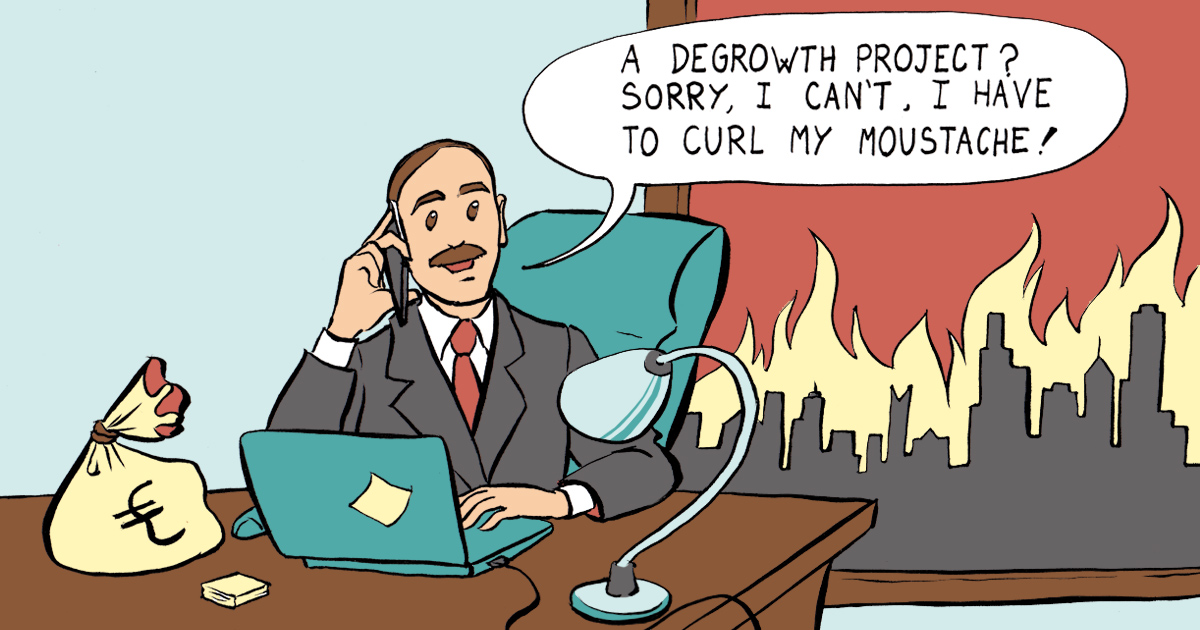

Cartoon created by Lorenza Luzzati

We are often inclined to assume that the world we live in is static and unchangeable; that it has always been the way we know it; and that the laws we empirically know are universally applicable even on a theoretical level.

Ascolta l'episodio 4 di Ritorno al futuro

Needless to say, this is not always the case. On the contrary, this narrative is often quite distant from 'true' reality, and yet meets an ancestral human need: that of understanding and dominating (or believing we do) the world around us, caging it in simple, uniform rules.

Case in point? Economic growth: that is, the pursuit of personal profit as the only objective to strive towards. A paradigm that - especially in the western world - permeates almost every aspect of the individual's life, imposing a worldview that is entirely focused on production and consumption, which are the only indicators of what is desirable and what is to be avoided.

Looking at history, however, one discovers that this economic configuration does not permeate across times or cultures, but is the result of a specific political-historical conjuncture and the concomitant emergence of a specific worldview.

As Susan Paulson, a professor at the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Florida, points out, «Almost no society throughout human history has been so focused on growth; on the contrary, if we look at the history of our species, we see that most of them have attempted to limit population growth and consumption levels in order to conserve available resources. The primary goal has been, in many cases, to try to avoid major changes, to maintain a balance».

«Of course», Paulson adds, «there have been many historical periods in which human societies have expanded: think of ancient Greece or the Roman Empire, for example. What we are experiencing today may well be considered one of those periods of rapid expansion. Studying human history allows us to recognise that this tendency is certainly not a universal and necessary event, but rather a historically situated phenomenon».

Growth – but till when?

What does ‘growth’ mean? The concept, which is today politically laden, actually indicates a natural process. Every living being, in fact, naturally experiences a period of growth; however, this period has a start and an end, and concludes in death and the release of organic matter to the biochemical cycles that keep the planet’s ecosystems alive.

«Only in the 20th century did the tendency to grow assume an economic significance», Professor Paulson points out. «At that time, in fact, the decline of many forms of spirituality was replaced by the rise of scientism. The concept of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was transformed from a mere technical tool into a kind of god, and has since been wielded as a weapon on many occasions: for example, during the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States, or in the obligatory ‘development’ (according to Western standards) imposed on the communities of the so-called Third World».

Thus, GDP growth has gradually become the only measure of the success or failure of nations, and every aspect of public and private life has been reduced to a variable of this omnipresent economic indicator. The main theoretical problem with GDP, however, is that it is based exclusively on the monetary value (which is determined by markets) of what is produced and consumed without due consideration of the means adopted to achieve it. Paradoxically, an inversion between means and ends occurs: if economic growth, stimulated by the continuous search for profit, is portrayed as the only means to achieve all desirable goals, then it will become the only true end from which all others descend. This is how, especially in recent decades, growth has steadily increased – albeit at an alarmingly slower pace, globally – at the expense of an increasing depletion of material resources and energy, with very high environmental and social costs.

Worldviews

The unsustainability of this system is now crystal clear: even the European Environmental Agency has recently admitted that there is a need to explore alternative ways to decouple the improvement of human well-being from such a burdening growth model.

Indeed, alternatives do exist: one is the well-known degrowth theory, of which Susan Paulson is a scholar and advocate: «Most proponents of ‘degrowth’ do not aim to trigger a general recession of the global economic system – an eventuality that would have disastrous consequences under current conditions – but believe it is necessary to rapidly reduce the amount of matter and energy depleted by human societies. The growing rate of transformation of these materials (and the waste resulting from these processes) has been closely linked to the increase in GDP for a long time; hence, the objective is to ‘decouple’ these two phenomena, and to find a different mode of existence in a finite world, in which the laws of thermodynamics cannot be ignored. It is, in other words, a theoretical challenge: to free ourselves from the obsession and idolatry of growth for its own sake».

Comics created by Lorenza Luzzati

«The Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci was right», Paulson recalls. «If workers and citizens were clearly made aware of all the sacrifices they have to undergo in order to foster growth, no one would accept such a state of affairs. Yet we have been convinced – a far more persuasive rhetorical strategy – that each of us is a key element in the functioning of a complex machinery. This has led to the supposed necessity to pursue growth being internalised and considered necessary to gain dignity and success, so that everyone is spontaneously offering major sacrifices at this altar».

And even if it turned out - as is finally happening - that this model of development is problematic and unjust, many would still be reluctant to abandon it. «Sometimes, change is difficult», Paulson concedes, «although it is clear that the status quo entails high levels of pain and injustice and leads us straight to a disastrous outcome. Many of the 'green' political agendas reflect this exact difficulty: they bring about economic and technical changes, but do not challenge any of the ideological principles underlying the current emergency. Instead, what alternative theories such as degrowth suggest is that, first and foremost, a renewal of values is needed, which should be implemented at all levels – from the individual to the global».

Possible futures

«It is also essential to work on education and information. If not properly understood, ‘degrowth’ can be frightening: how is it possible to preserve our standard of living if there is no longer constant economic growth to sustain it? Put in these terms, the question seems misleading. We should rather explain to the 'average citizen' that the alternative to endless economic growth is a different worldview and a new configuration of society; that we can start imagining a different future, made of conviviality, sharing, and caring, rather than growth».

At present, such scenarios are just about utopia. The effects of the continued prevalence of a profoundly unsustainable model of development are already affecting our lives – think of the pandemic, the increasingly evident effects of climate change, the numerous resource wars that are breaking out all over the world. Yet, there are also signs of hope: «There are many ‘convivial’ realities and experiences, communities where the primary objective is not material growth. Many of these are traditional communities, which preserve beliefs and rituals that emphasise the intimate bond between man and the natural world, which as such is worthy of rights and respect. There are also many experiments underway, some of them highly innovative, which are exploring new paths. I am not sure that, given the limited time available, we will be able to stop or slow down the train we are on; but my hope is that at least some of us will be able to get off the track, and embark on alternative paths».

We must dare to change direction: stop pursuing the current utopia that promises infinite growth even in a finite world, and move towards new utopias in which human society succeeds in living in harmony with the natural environment, which surrounds and hosts us.

ALSO READ:

- Back to the future. Georgescu-Roegen and the origins of ecological economics

- Back to the future. Human and non-human world, incommensurability of values

- Back to the future. The human society as an organism

- Back to the future. Prosperity, conviviality, sharing: For a gentle degrowth

- Back to the Future. Sustainable Development Goals and the sustainability framework: An open debate

- Back to the future. Sustainability is a political choice

- Back to the future. Environmentalism is a social issue

- Back to the future. Fuzzy, incomplete, plural: the world beyond hegemonies

- Back to the future. Actualizing the potential for socio-ecological change

- Back to the future. On waste pickers

- Back to the future. Implementing ecological economics: regional perspectives

- Back to the future. Valuing nature beyond money: from price tags to plural valuation languages

- Back to the future. The importance of complexity

- Back to the future. Healing our addiction to growth

- Back to the future. Herman Daly: the economy as a common good