IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Oceania

Australia is a global power in the carbon industry, and is the third largest exporting country of fossil fuels. Prime minister Scott Morrison is well known for adopting a “technological” approach to climate change, which consists in advocating for emissions reduction while minimizing changes to production systems and lifestyles and focusing on mitigation technologies such as carbon capture and geoengineering.

Before the COP26 in Glasgow in November 2021, Australia’s climate commitments were deemed largely insufficient. By the end of October 2021, Australia declared for the first time its intention to align to complete decarbonization by 2050. Yet, it appears to plan achieving this goal primarily through investments in technological solutions, whose effectiveness is yet to be fully demonstrated, and little else.

Despite this, Australia is particularly vulnerable to some effects of global warming and climate change, especially wildfires.

Ongoing global warming will lead to an increase in warm days and a decrease in cold days across Oceania. it will also cause glacier retreat, sea-level rise, and ocean acidification. More wildfires are expected in southern and eastern Australia, as well as northern and eastern New Zealand. While rainfall intensity will increase, droughts will also become more frequent in southern and eastern Australia and northern New Zealand.

Climate impacts will have cascading effects across all socio-economic sectors and natural systems. Interconnections between sectors are complex and will generate new types of risk, further limiting adaptation options. An example is the consequences experienced by various sectors and their infrastructures following the 2019-2020 wildfire season in southeast Australia.

The report edited by the IPCC Working Group 2 (AR6 WG2) on the vulnerabilities of social and natural systems to the impacts of climate change and their adaptive capacities identified nine key risks for Oceania.

Extreme weather events, intensified and made more frequent by climate change, have already caused deaths and damages in Oceania. Heatwaves, floods, storms, and fires have impacted ecosystems, strained infrastructure and essential services, disrupted food production, affected entire national economies, and compromised jobs.

Ecosystems

Combined with some vulnerabilities, climate change and extreme weather events have had severe impacts on Australian and New Zealand ecosystems, some of which are irreversible. A rodent endemic to Bumble Cray, a small coral reef island, known as Melomys rubicola, has been declared extinct in 2016 due to habitat loss caused by rising sea levels and storms in Torres Strait. This is considered the first documented extinction of a mammal species due to climate change.

Widespread coral bleaching events and the loss of marine ecosystems known as kelp forests have already been caused by ocean warming and marine heatwaves.

Human society

Similarly, climate change and extreme weather events have exacerbated some vulnerabilities within human societies. The socio-economic costs due to climate variability have increased. Heatwaves have raised mortality rates and the incidence of several diseases. Drought has caused financial distress in agricultural estates and rural areas. Coastal flooding has intensified due to rising sea levels, compounded by high tides and storms. Also tourism has been impacted by coral bleaching, wildfires, and glacier retreat.

Nine key risks

- Loss and degradation of coral reefs, their associated biodiversity and ecosystem services in Australia, due to ocean warming and marine heatwaves.

- Loss of alpine biodiversity in Australia due to reduced snowfall.

- Transition or collapse of ‘alpine ash’(Eucalyptus delegatensis), snow gum (Eucalyptus pauciflora), pencil pine (Athrotaxis cupressoides), and jarrah forests (Eucalyptus marginata) in southern Australia, caused by hotter and drier conditions and increased wildfires.

- Loss of kelp forests in southern Australia and southeastern New Zealand due to ocean warming, marine heatwaves, and overgrazing from expanding ranges of herbivorous fish and sea urchins driven by climate change.

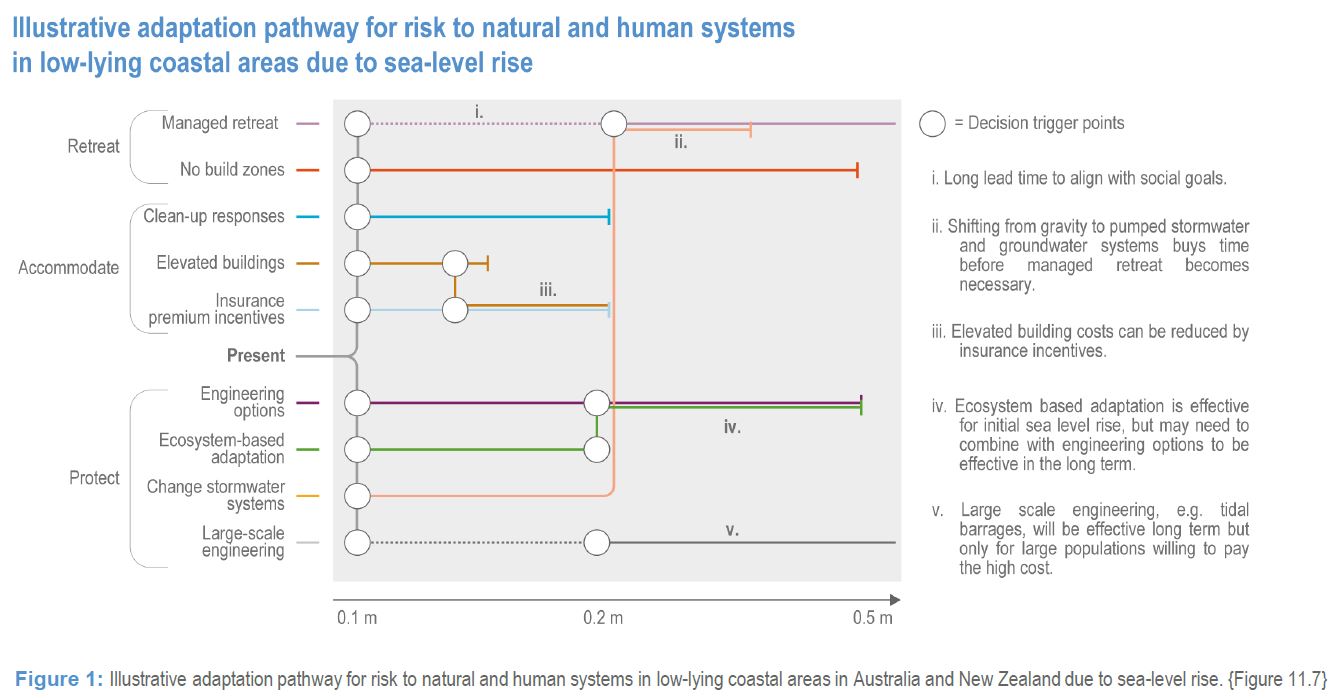

- Loss of natural and human systems in low-lying coastal areas do to rising sea levels.

- Disruption and decline in agricultural production and increased stress on rural communities in southwestern, southern and eastern continental Australia due to warmer and drier conditions.

- Increased mortality due to heat and prevalence of diseases affecting both humans and wildlife in Australia.

- Cascading impacts on cities, settlements, infrastructure, supply chains, and services due to wildfires, floods, droughts, heatwaves, storms, and rising sea levels.

- Inability of institutions and government systems to effectively address climate risks.

Figure 1 IPCC AR6 WG2 Fact Sheet Oceania

Obstacles to adaptation

Despite ambitions to implement adaptation solutions is growing among governments, non-governmental organizations, businesses, and communities, progress remains uneven due to various barriers. These include a lack of continuity in political leadership, conflicting goals, diverging values and risk perceptions, knowledge limitations and lack of information, fear of litigation, lack of engagement, trust, and resources.

For some ecosystems that are near critical thresholds, further climate change could lead to irreversible damage, drastically reducing the opportunities for adaptation. Regarding human systems, limits to adaptation include critical temperature thresholds, drinking water availability, and the inability of some low-lying coastal areas to adapt.

Adaptation options

Measures that underestimate current climate risks can lead to maladaptations and undermine society’s ability to respond to future impacts. Already available tools can strengthen decisions to address climate change, including proactive planning, coordination across government levels and sectors, institutional agreements, government leadership, accessible information at the national level, and adaptation funding.

It is crucial to focus on the role that social inequalities and ecosystem degradation can play in generating vulnerabilities. Islanders and Aboriginal peoples of the Torres Strait, as well as the Maori Tangata Whenua (the people of the land), can contribute to effective adaptation by sharing their knowledge regarding on comprehensive planning to promote collective action and mutual support among regions.

Global warming projected under current emission reduction policies would expose many parts of Oceania’s natural and human systems to high levels of risk, beyond their adaptive capacities. Delays in implementing emission reduction solutions will hinder sustainable and resilient economic development, leading to further impacts and increased adaptation costs. Mitigating climate risks requires rapid emission reductions to keep global warming below 2°C, alongside swift and robust adaptation measures.

This article was translated into English by Sofia Belardinelli. The original version of this article is available here.

ALSO READ:

- IPCC: Nearly direct correlation between emissions and global warming

- IPCC: Impacts of climate change are not equal for everyone

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Africa

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Europe

- IPCC: The impact of climate change on small islands

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Asia

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Oceania

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on Central and South America

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on North America

- IPCC: The impacts of climate change on human settlements

- IPCC Synthesis Report: every fraction of a degree matters